The Problem with Seed Oils

For decades, we’ve been told the same story: seed oils like soybean, canola, sunflower, and corn oil are “heart-healthy” replacements for traditional fats like butter and tallow. They’re recommended by guidelines, marketed as cholesterol-friendly, and used in almost every restaurant fryer in the country. So if they’re everywhere, how could they be a problem?

The answer lies in their chemistry. Seed oils are extremely high in linoleic acid, an omega-6 fat that breaks down easily when exposed to heat, oxygen, or light. During cooking, processing, and even inside the body, linoleic acid oxidizes into reactive aldehydes and lipid peroxides — compounds known to damage DNA, disrupt mitochondria, and promote inflammation. This isn’t alternative theory; it’s basic biochemistry.

Human research supports this. In the reanalysis of the Sydney Diet Heart Study, replacing natural fats with high-linoleic safflower oil actually increased mortality, despite lowering cholesterol. And in a controlled trial, reducing dietary linoleic acid for just twelve weeks lowered oxidized LA metabolites in the bloodstream — direct evidence that cutting seed oils reduces oxidative stress.

This article breaks down the common seed oils one by one — soybean, canola, sunflower, safflower, corn, grapeseed, cottonseed, and peanut oil — and shows exactly which are the most unstable and why. By the end, you’ll know which ones to avoid, which are slightly less harmful, and why their fatty-acid profiles matter so much for long-term health.

Related Article: Are Seed Oils Bad For You

Seed Oils to Avoid

Soybean Oil

Soybean oil is the most widely consumed seed oil in the United States and a major source of omega-6 linoleic acid (LA) in the modern diet. It’s used in nearly every processed food — from salad dressings and sauces to fast-food fryers — and is often promoted as a “heart-healthy” alternative to saturated fat. But its high LA content and industrial refinement make it one of the most oxidation-prone oils in use today.

Animal studies have repeatedly shown that diets rich in soybean oil disrupt metabolic and neurological health. In a controlled experiment at the University of California, mice fed soybean oil developed more obesity, insulin resistance, and fatty-liver damage than those fed coconut oil or even fructose — despite identical calories. The oil altered hundreds of genes related to metabolism, inflammation, and the brain.

A 2024 study found similar results: at equal calorie levels, soybean oil produced far stronger oxidative stress and neuroinflammation than lard, activating inflammatory signaling and damaging the gut barrier and microbiome.

Quite a few studies do show that soybean oil lowers LDL cholesterol, but this change reflects altered cholesterol transport, not reduced arterial oxidation or inflammation, the real culprits of heart disease. In fact, the LA-rich LDL particles produced by soybean oil are more easily oxidized into oxLDL, which plays a direct role in plaque formation and endothelial injury.

Mechanistically, soybean oil carries the same risks that define most seed oils — high polyunsaturated instability, a strong omega-6 bias, and the tendency to form reactive lipid peroxides when heated or stored. Among common cooking oils, it ranks as one of the least stable and most inflammatory when used frequently.

Bottom line: Among all common seed oils, soybean oil ranks near the very bottom — extremely high in linoleic acid, highly oxidizable, and consistently associated with metabolic and inflammatory disruption in both animal and human research.

| Property | Soybean Oil | Context / Meaning |

| Saturated fat (SFA) | ~14 % | Low saturation → higher instability |

| Monounsaturated fat (MUFA) | ~24 % | Moderate |

| Polyunsaturated fat (PUFA) | ~58 % | Very high — mostly linoleic acid (LA) |

| Omega-6 : Omega-3 ratio | ~10 : 1 – 12 : 1 | Strong pro-inflammatory bias |

| Smoke point | ~450 °F (232 °C) | High, but oxidation rises with reuse |

| Oxidative Stability Index (OSI) | ~5 hours @ 110 °C | Poor — degrades quickly under heat |

| Trans-fat (post-refining) | ≤ 0.5 % | Trace amounts formed during hydrogenation |

Corn Oil

Corn oil is often promoted as a heart-healthy alternative to saturated fat because it lowers LDL cholesterol. While this may be true, the modern literature now does not correlate lower LDL to a lower risk of heart disease. Even if it did, the moderate decreases in LDL still seem to be massively outweighed by their harm from inflammation and oxidation.

One of the most cited studies in favor of seed oils such as corn oil is a large Harvard meta-analysis of observational data. Here, the study found that people reporting higher intakes of linoleic acid — the main omega-6 fat in corn oil — had about a 15% lower risk of coronary events.

However, this was an observational study, not a controlled clinical trial. People who chose vegetable oils were typically more health-conscious to begin with — they exercised more, smoked less, and generally followed healthier lifestyles.

These behaviors, rather than the oils themselves, could easily explain the lower heart-disease risk observed in the data. Ironically, these positive habits may have masked any potential harm from the seed oils themselves, creating the illusion of a benefit where none actually existed.

When corn oil was actually tested in randomized controlled trials, the results told a different story. In the Minnesota Coronary Experiment, replacing saturated fat with corn oil and corn-oil margarine lowered serum cholesterol but did not reduce mortality; in fact, greater cholesterol lowering correlated with a slightly higher risk of death.

Likewise, the Rose Corn Oil Trial found that post-heart-attack patients told to consume large amounts of corn oil experienced more cardiac events and deaths than controls.

Mechanistically, corn oil’s high linoleic-acid content makes it prone to oxidation. Oxidized linoleic-acid metabolites (OXLAMs) promote oxidative stress and inflammation — both key drivers of atherosclerosis.

Lowering dietary LA has been shown to reduce circulating OXLAMs in humans, supporting the view that excessive omega-6 intake can create a pro-inflammatory environment even when LDL appears improved.

Overall, the best-controlled evidence suggests that while corn oil can reduce LDL cholesterol, it has not been shown to reduce heart-disease or overall mortality, and its chemical instability raises valid concerns about long-term health effects.

Bottom line: Corn oil sits firmly in the “avoid” category — high in linoleic acid, unstable under heat, and repeatedly shown in controlled trials to lower cholesterol without improving, and sometimes worsening, real clinical outcomes.

| Property | Corn Oil | Context / Meaning |

| Saturated fat (SFA) | ~13 % | Low → less stable under heat |

| Monounsaturated fat (MUFA) | ~28 % | Moderate |

| Polyunsaturated fat (PUFA) | ~58 % | Extremely high — mostly linoleic acid (LA) |

| Omega-6 : Omega-3 ratio | ~80 : 1 – 83 : 1 | Extremely skewed; highest among seed oils |

| Smoke point | ~450 °F (232 °C) | Similar to soybean, but forms peroxides when reused |

| Oxidative Stability Index (OSI) | ~6 hours @ 110 °C | Slightly better than soybean, still poor |

| Trans-fat (post-refining) | ≤ 0.5 % | Trace levels from industrial processing |

Canola (Rapeseed) Oil

Canola oil was developed in the 1970s as a low-erucic-acid version of rapeseed oil and quickly became marketed as a “heart-healthy” alternative to saturated fats. It’s now one of the most widely used cooking oils in North America — second only to soybean oil.

Like other seed oils, it’s extracted through high-temperature refining and solvent processing, and it contains around 60% monounsaturated fat (mostly oleic acid), 30% polyunsaturated fat, and about 7% saturated fat.

One of the most frequently cited papers in favor of canola oil is a 2013 review published in Nutrition Reviews. The review — funded by the Canola Council of Canada and the U.S. Canola Association — concluded that canola oil “reduces total and LDL cholesterol” compared to diets higher in saturated fat, and therefore may help reduce heart disease risk.

However, the logic here mirrors the same outdated reasoning seen in earlier seed-oil research:

Lower LDL cholesterol is automatically assumed to mean lower heart-disease risk.

The problem is that this assumption hasn’t aged well. Lowering LDL cholesterol by dietary fat substitution doesn’t necessarily translate into better cardiovascular outcomes — especially when those unsaturated fats are highly prone to oxidation. None of the trials included in this review measured oxidative stress, inflammation, or atherosclerosis progression directly. They focused only on short-term blood-lipid changes (often under eight weeks) — surrogate markers, not hard outcomes.

Modern research shows that oxidized LDL, not total LDL, plays a more decisive role in atherosclerosis. And canola oil’s high proportion of polyunsaturated fats — mainly linoleic acid — makes its LDL particles more susceptible to oxidation, not less. So while LDL levels may drop slightly on paper, the biological risk profile can worsen in the long term.

Beyond cardiovascular markers, newer evidence has raised other concerns. A 2017 Nature Scientific Reports study found that mice fed a canola-enriched diet for six months experienced impaired memory, reduced synaptic proteins, and an increase in amyloid-β 42/40 ratios — changes linked with Alzheimer’s pathology.

While this was an animal study and can’t be generalized directly to humans, it challenges the assumption that canola oil offers the same neuroprotective benefits as olive oil, despite having a similar fatty-acid profile.

In practice, canola’s health impact depends heavily on processing and use. Cold-pressed canola oil used unheated may be relatively benign, but the refined, bleached, and deodorized (RBD) version commonly sold in supermarkets is often oxidized before you even cook with it.

Once heated, especially for frying, the oxidation accelerates further, forming aldehydes and OXLAMs — compounds known to promote inflammation.

Bottom line: Canola oil is one of the least harmful industrial seed oils on paper, but once refined and heated it still behaves like a typical high-PUFA oil — not ideal, but less damaging than soybean, corn, safflower, sunflower, or grapeseed oil.

Canola (Rapeseed) Oil — Quick Profile

| Marker | Value / Description | Why It Matters |

| Saturated Fat (SFA) | ~7% | Low level → more “heart-friendly,” but less stable under heat. |

| Monounsaturated Fat (MUFA) | ~60% (mostly oleic acid) | Moderately heat-resistant; similar to olive oil in MUFA type. |

| Polyunsaturated Fat (PUFA) | ~30% | Higher reactivity → prone to oxidation when heated or stored long-term. |

| Omega-6 : Omega-3 Ratio | ~2 : 1 (raw) → ~8 : 1 after cooking | Favorable on paper, but omega-3s (ALA) degrade quickly with heat. |

| Smoke Point | ~205 °C / 400 °F | Suitable for medium-heat cooking; oxidation increases above this. |

| Oxidative Stability Index (OSI) | ~10–15 hours @ 110 °C | Moderate stability — better than soybean/corn, worse than olive/coconut. |

Sunflower Oil

Sunflower oil is often marketed as a light, “heart-healthy” cooking oil — but its health impact depends heavily on the type of sunflower oil and how it’s used.

Most supermarket varieties are the high-linoleic form, made up of nearly all omega-6 polyunsaturated fats (PUFAs), mainly linoleic acid (LA). These fats are extremely unstable under heat and light, breaking down into oxidative byproducts that promote inflammation and metabolic stress.

A 2012 study tested sunflower oil in mice fed either a normal or high-fat diet. While the oil slightly improved cholesterol levels, it did not prevent insulin resistance or inflammation — and even in the normal-diet group, sunflower oil reduced insulin sensitivity and increased inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α. The researchers concluded that sunflower oil’s high linoleic acid content led to pro-inflammatory and insulin-disrupting effects, despite its apparent benefit on lipids.

These findings align with what’s known biochemically: linoleic acid easily oxidizes, forming reactive aldehydes and lipid peroxides that damage cell membranes and mitochondria. This means sunflower oil behaves much like soybean or corn oil in the body — lowering LDL cholesterol on paper while increasing oxidative and inflammatory stress.

However, not all sunflower oils are equal. There are three main types:

- High-linoleic sunflower oil (≈ 65–70% LA): The standard, cheap supermarket version. Avoid for regular use — highly unstable and pro-inflammatory.

- Mid-oleic (NuSun): Modified for higher oleic acid (MUFA ~60%, LA ~25%). More stable and less inflammatory, though still refined and oxidizes with repeated heating.

- High-oleic sunflower oil: Closest to olive oil in composition (MUFA ~75–80%). Much more stable and far less prone to oxidation. It’s the least harmful option if sunflower oil must be used.

Bottom line: Regular high-linoleic sunflower oil is among the most unstable cooking fats available and should be avoided; only the high-oleic varieties meaningfully escape the problems seen with other high-PUFA seed oils.

| Property | High-Linoleic Sunflower Oil | Context / Meaning |

| Saturated fat (SFA) | ~10 % | Low → highly reactive |

| Monounsaturated fat (MUFA) | ~20 % | Low in the regular type |

| Polyunsaturated fat (PUFA) | ~68 % | Very high — mostly omega-6 LA |

| Omega-6 : Omega-3 ratio | ~200 : 1 | One of the worst imbalances |

| Smoke point | ~440 °F (227 °C) | High, but oxidation begins early |

| Oxidative Stability Index (OSI) | ~3–4 hours @ 110 °C | Very poor — breaks down quickly |

| Trans-fat (post-refining) | ≤ 0.5 % | Trace levels from processing |

Safflower Oil

Safflower oil is one of the highest-linoleic-acid oils available, with roughly 70–75% linoleic acid (LA) — even higher than sunflower, corn, or soybean oil. It’s less common as a standalone cooking oil but widely used in salad dressings, processed foods, “vegetable oil blends,” and industrial frying due to its neutral taste and low cost.

Like other seed oils, safflower oil is typically extracted through refining, bleaching, and deodorizing, making it highly vulnerable to oxidation both on the shelf and especially when heated. Its extremely high LA content makes it one of the least stable oils in supermarket circulation.

A frequently referenced human trial in support of safflower oil found that supplementing 8 g/day for 16 weeks improved some markers—HbA1c, fasting glucose, CRP, HDL—but only in obese, postmenopausal women with poorly controlled diabetes. The study did not measure oxidized LDL, OXLAM formation, or long-term cardiovascular outcomes, and the small improvements likely resulted from minor reductions in trunk fat—something that improves metabolic markers regardless of the type of fat consumed.

Animal research is mixed: some studies show slight reductions in certain fat depots when cold-pressed safflower oil is combined with exercise, while others show worsened lipid profiles or no meaningful metabolic benefit. Importantly, these studies use unheated, cold-pressed oil—not the refined safflower oil found in processed foods and fryers.

When comparing safflower oil to other common seed oils, it consistently lands near the bottom of the list:

- More linoleic acid than soybean, corn, and sunflower

- Lower oxidative stability than almost all major cooking oils

- Among the fastest to oxidize when heated

- Produces large amounts of OXLAMs and aldehydes during frying

Cold-pressed safflower oil used unheated may be less harmful, but the refined supermarket version is one of the least ideal oils for cooking, frying, or regular consumption.

Bottom line: With one of the highest linoleic-acid contents of any oil, safflower oil is one of the least stable and most oxidation-prone fats on the market — firmly in the “avoid entirely” category.

| Property | Safflower Oil (High-Linoleic) | Context / Meaning |

| Saturated fat (SFA) | ~7% | Very low → contributes to instability under heat |

| Monounsaturated fat (MUFA) | ~13–15% | Low → far less stable than high-oleic oils |

| Polyunsaturated fat (PUFA) | ~70–75% | Extremely high — one of the highest PUFA oils available |

| Linoleic acid (LA) | ~70–75% | Among the highest LA concentrations of any cooking oil |

| Omega-6 : Omega-3 ratio | ~200 : 1+ | Virtually no omega-3s; very pro-inflammatory balance |

| Smoke point | ~225–230 °C (437–446 °F) | Looks high, but oxidation begins long before smoke point |

| Oxidative Stability Index (OSI) | Very low (faster oxidation than soybean, corn, sunflower) | One of the fastest oils to oxidize during heating or storage |

| Trans-fat (post-refining) | ≤ 0.5% | Trace amounts from industrial processing |

Cottonseed Oil

Cottonseed oil is a byproduct of the cotton industry that became popular in the early 20th century as a cheap replacement for traditional fats. It’s heavily refined, bleached, and deodorized, and today it’s found mostly in processed foods and commercial deep-fryers rather than home kitchens. Its appeal isn’t nutritional — it’s economic. Cottonseed oil is inexpensive, neutral-tasting, and available in huge quantities, which is why food manufacturers and restaurants rely on it.

Cottonseed oil is often framed as “heart-healthy” due to its low saturated fat content, but that overlooks its high linoleic acid level (around 50%), which makes it relatively unstable under heat and prone to oxidation. Comparative studies show cottonseed oil performs worse in oxidative stability testing than canola oil and far worse than high-oleic oils.

Another consideration is gossypol, a naturally occurring compound in cotton plants. Commercial refining removes most of it, but its presence underscores the fact that cotton wasn’t bred as a food crop — the oil is simply a convenient way for the industry to monetize a byproduct.

Like other high-PUFA seed oils, cottonseed oil can modestly lower LDL cholesterol when replacing saturated fat in controlled studies. But these short-term biomarkers don’t translate into clear long-term health benefits, and mechanistic research suggests higher-LA oils generate more oxidation products during heating.

Most people don’t cook with cottonseed oil at home. Instead, it enters the diet in two places:

- Processed foods: chips, crackers, packaged baked goods, frostings, icings, peanut-butter stabilizers, and shelf-stable snacks

- Restaurants: especially fast-food and high-volume kitchens, where it’s used as a low-cost deep-fryer oil or blended with other seed oils

In other words, if someone regularly eats packaged snacks or fried foods, cottonseed oil is almost unavoidable.

While not as extreme in linoleic acid as safflower or sunflower oil, cottonseed oil combines high PUFA content with one of the most aggressive refining processes — not a favorable combination for cooking or regular consumption.

Bottom line: Cottonseed oil combines high linoleic acid with heavy industrial refining, giving it poor stability and little nutritional value — a lower-tier seed oil that’s best avoided, especially in processed snacks and deep-fried foods.

| Property | Cottonseed Oil | Context / Meaning |

| Saturated fat (SFA) | ~25% | Higher SFA than most seed oils, but still heavily refined and unstable overall |

| Monounsaturated fat (MUFA) | ~20% | Moderate; provides some stability but overshadowed by high PUFA content |

| Polyunsaturated fat (PUFA) | ~55% | High PUFA → prone to oxidation, especially during frying |

| Linoleic acid (LA) | ~50% | Main driver of instability; oxidizes quickly under heat |

| Omega-6 : Omega-3 ratio | ~200 : 1 | Extremely skewed; virtually no omega-3 content |

| Smoke point | ~420°F (refined) | Industrially refined to raise smoke point, but oxidation still occurs early |

| Oxidative Stability / OSI | Low | High-PUFA + aggressive refining → poor real-world heat stability |

| Trans-fat (post-refining) | ≤ 0.5% | Trace amounts from bleaching/deodorizing processes |

Grapeseed Oil

Grapeseed oil is extracted from the seeds left over after winemaking — a byproduct that was historically considered waste. Modern refining techniques made it possible to turn these seeds into a low-cost, neutral-tasting cooking oil.

Over the last two decades, it has gained popularity in home kitchens and high-end restaurants, often marketed as a “light,” “clean,” or “high-smoke-point” alternative to olive oil.

Despite the healthy branding, grapeseed oil is one of the highest-PUFA seed oils available, and its composition makes it poorly suited for high-heat cooking.

Grapeseed oil is made up of roughly 70–75% linoleic acid (LA) — a higher concentration than canola, soybean, and cottonseed oil, and similar to high-LA safflower or sunflower oil. This extremely high omega-6 content makes grapeseed oil highly susceptible to oxidation, especially when heated. Studies comparing common culinary oils consistently show grapeseed oil producing more oxidation byproducts and aldehydes during frying than oils higher in monounsaturated fat.

While some small studies report modest improvements in cholesterol markers when grapeseed oil replaces saturated fat, these short-term blood lipid changes do not necessarily predict long-term outcomes — a pattern seen across most high-LA seed oils.

From a stability perspective, grapeseed oil breaks down significantly faster under heat than olive oil, avocado oil, or even standard canola oil.

Grapeseed oil is favored in cooking and manufacturing for reasons unrelated to health:

- Cheap byproduct of the wine industry

- Neutral flavor, making it appealing for salad dressings and mayonnaise

- Heavily refined, which increases shelf life

- Marketed as a “high-smoke-point” oil, even though smoke point does not predict oxidative stability

You’ll find grapeseed oil in some upscale restaurant kitchens, packaged vinaigrettes, chips, crackers, and natural/organic snack foods — where its neutral flavor is preferred over stronger oils like olive.

On the “worst oils” scale, grapeseed oil ranks near the very top. It contains an extremely high linoleic-acid content (~70–75%), has very low oxidative stability despite its marketed smoke point, requires heavy industrial refining to extract, and is often used in high-heat cooking — exactly where it breaks down the fastest.

Bottom line: With extremely high linoleic acid, very low oxidative stability, and heavy industrial processing, grapeseed oil may be the single worst seed oil for routine cooking, especially when heated.

| Property | Grapeseed Oil | Context / Meaning |

| Saturated fat (SFA) | ~9% | Very low → minimal heat stability |

| Monounsaturated fat (MUFA) | ~16% | Low; offers little resistance to oxidation |

| Polyunsaturated fat (PUFA) | ~75% | Extremely high — one of the most PUFA-rich oils available |

| Linoleic acid (LA) | ~70–75% | Main driver of instability; oxidizes rapidly when heated |

| Omega-6 : Omega-3 ratio | ~700 : 1 | One of the most skewed fatty-acid ratios of any culinary oil |

| Smoke point | ~420°F (refined) | High on paper, but misleading — oxidation occurs long before smoke point |

| Oxidative Stability / OSI | Very |

Rice Bran Oil

Rice bran oil is extracted from the outer layer of rice grains — a byproduct of the milling process that was industrially refined into a low-cost cooking oil. It’s widely used in Asian cuisine, packaged snack foods, and commercial fryers, and is often promoted as a “heart-healthy” oil with a high smoke point. But its fatty-acid profile and real-world usage make it far less stable than the marketing suggests.

Animal and food-chemistry studies consistently show that rice bran oil forms significant oxidation products during standard cooking conditions. In comparative heating tests, refined rice bran oil generates aldehydes and lipid peroxides at levels similar to soybean and corn oil, especially when used for deep frying — the exact setting where it’s most widely used.

Although unrefined rice bran oil contains γ-oryzanol (an antioxidant complex), the refined versions used in restaurants lose most of these protective compounds.

Human trials show that replacing saturated fat with rice bran oil can modestly lower LDL cholesterol, but this matches the same pattern seen across most high-PUFA seed oils. These LDL changes do not reflect improved oxidative or inflammatory status, and the LA-rich LDL particles generated are more prone to oxidation — a central mechanism in atherosclerotic damage.

Mechanistically, rice bran oil carries the same vulnerabilities as other industrial seed oils: moderate-to-high linoleic acid (32–38%), rapid oxidation under heat, and heavy refinement that strips away stabilizing antioxidants. Its widespread use in deep fryers — where oils are heated repeatedly and exposed to oxygen — makes its oxidation potential especially relevant in everyday eating.

Rice bran oil is popular in restaurants because it’s cheap, neutral, and marketed as heat-stable — not because it’s inherently healthy. With one-third of its fat as linoleic acid and a refining process that removes most natural antioxidants, it oxidizes quickly under the high-heat conditions where it’s most commonly used. More stable fats such as olive oil, avocado oil, butter, or tallow remain better options for everyday cooking.

See this article here for true healthy fats and oils to use for cooking.

Bottom line: Rice bran oil isn’t as extreme in LA as the worst offenders, but its instability during frying and heavy use in restaurant deep fryers make it a poor choice compared to more stable, low-PUFA fats.

| Property | Rice Bran Oil | Context / Meaning |

| Saturated fat (SFA) | ~20% | Moderate saturation → somewhat stable, but overshadowed by high PUFA |

| Monounsaturated fat (MUFA) | ~40% | Provides some oxidative stability but not enough for deep frying |

| Polyunsaturated fat (PUFA) | ~35–40% | High PUFA → oxidizes rapidly when heated, especially in fryers |

| Linoleic acid (LA) | ~32–38% | Main reactive component → forms aldehydes and lipid peroxides during cooking |

| Omega-6 : Omega-3 ratio | ~25 : 1 | Highly imbalanced; moderate-linoleic but still heavily omega-6 dominant |

| Smoke point | ~450°F (refined) | High on paper, but antioxidants are removed during refining → oxidation still accelerates early |

| Oxidative Stability / OSI | Low–moderate (drops sharply during frying) | Loses stability quickly with repeated heating; forms oxidation byproducts similar to soybean/corn |

| Trans-fat (post-refining) | ≤ 0.5% | Trace levels from industrial refining and deodorization |

Sesame Oil

Sesame oil has been used for thousands of years in Middle Eastern and Asian cuisines, traditionally pressed from sesame seeds using minimal processing. In its classic, unrefined form, sesame oil is used sparingly — mostly as a finishing oil or flavor enhancer — and contains natural antioxidants (sesamin, sesamol, sesamolin) that make it surprisingly stable relative to other seed oils.

Modern industrial sesame oil, however, is a different product. Today, most commercially available sesame oil — especially the versions used in restaurants — is highly refined, bleached, and deodorized, which removes the protective antioxidants and leaves behind a more unstable, high-linoleic-acid oil similar to other seed oils.

Because sesame oil sits at the intersection of traditional food and modern refining, it needs a more nuanced evaluation than typical seed oils.

Unrefined sesame oil contains a unique set of polyphenols (sesamol, sesamin) that slow oxidation and may provide metabolic benefits when used in small quantities. But the picture changes with refined sesame oil, which loses most of these stabilizing compounds.

Refined sesame oil is typically around 40–45% linoleic acid (LA) — lower than grapeseed or sunflower, but still high enough to oxidize when heated repeatedly. Studies comparing refined sesame oil to other cooking oils show that it forms oxidation byproducts and aldehydes more readily when used for frying, performing similarly to soybean and corn oil under high-heat conditions.

Traditional sesame oil, used in small amounts at low heat, doesn’t pose the same oxidation concerns. The problem arises when refined sesame oil is used as a primary cooking fat, particularly in commercial kitchens.

Most home cooks use sesame oil for flavoring, not frying — which keeps intake low.

But refined sesame oil is increasingly used where people don’t see the label:

- Restaurant stir-fries and woks

- Asian fast-casual chains

- Fryer blends mixed with soybean, rice bran, or canola

- Packaged sauces, marinades, and dressings

- Snack foods marketed as “Asian-inspired”

In these contexts, sesame oil is exposed to high heat or repeated frying cycles, where oxidation accelerates.

Sesame oil doesn’t belong at the absolute top of the “worst oils” list, but refined sesame oil does carry risks when used for high-heat cooking

Bottom line: Traditional sesame oil used sparingly is far less concerning, but refined sesame oil used for high-heat cooking behaves much like other unstable seed oils — a moderate-risk option that becomes problematic in restaurant settings.

| Property | Sesame Oil (Refined) | Context / Meaning |

| Saturated fat (SFA) | ~14% | Moderate; offers some stability but overshadowed by high LA |

| Monounsaturated fat (MUFA) | ~41% | Helps stability slightly, but not enough to offset PUFA oxidation |

| Polyunsaturated fat (PUFA) | ~45% | High PUFA content → prone to oxidation during heating |

| Linoleic acid (LA) | ~40–45% | Primary driver of oxidative instability in refined sesame oil |

| Omega-6 : Omega-3 ratio | ~140 : 1 | Very skewed; contributes to inflammatory imbalance |

| Smoke point | ~410°F (refined) | Looks decent, but oxidation begins long before smoke point |

| Oxidative Stability / OSI | Moderate when unrefined; low when refined | Refining removes sesamin/sesamol antioxidants → oil oxidizes faster |

| Trans-fat (post-refining) | ≤ 0.5% | Trace levels created during high-heat deodorizing |

Peanut Oil

Peanut oil is widely used in restaurants and home kitchens because it has a high smoke point, neutral flavor, and good frying performance. It’s often marketed as a “heart-healthy” oil due to its monounsaturated fat content — but like most seed oils, the full picture depends on its fatty acid profile, processing, and how it behaves under heat.

Despite being slightly more stable than soybean, corn, or sunflower oil, peanut oil still contains a significant amount of linoleic acid (LA), the omega-6 PUFA that oxidizes easily and forms inflammatory byproducts during frying.

Most supermarket peanut oil is the refined, high-PUFA type. “Gourmet” unrefined peanut oil exists, but it’s unsuitable for high-heat cooking and still carries the same fundamental PUFA burden.

When peanut oil is heated repeatedly — as in restaurant fryers — its linoleic-acid content breaks down rapidly into lipid-peroxidation products and toxic aldehydes such as 4-HNE, MDA, and acrolein. These compounds impair antioxidant defenses and trigger inflammatory responses in animal models. Like other high-PUFA seed oils, peanut oil becomes increasingly unstable and reactive with each heating cycle, especially under commercial frying conditions.

Peanut oil is often called “healthy” because it contains a relatively high amount of MUFAs. But its 30–35% linoleic acid content still creates the same oxidative instability issues that make seed oils problematic.

Bottom line: Peanut oil is mid-tier — more stable than soybean or corn oil, but still high enough in linoleic acid to oxidize quickly under heat, making it a poor choice for frequent frying even if it’s “better than most seed oils.”

| Property | Peanut Oil | Context / Meaning |

| Saturated fat (SFA) | ~17% | More stable than many seed oils, but still mostly unsaturated |

| Monounsaturated fat (MUFA) | ~46–50% | Helps stability; similar to mid-oleic oils |

| Polyunsaturated fat (PUFA) | ~32–35% | High enough to oxidize during frying |

| Omega-6 : Omega-3 ratio | ~150–200 : 1 | Extremely imbalanced — nearly pure linoleic acid |

| Smoke point | ~450°F (232°C) | High, but misleading — oxidation begins long before smoke point |

| Oxidative Stability Index (OSI) | ~6–7 hours @ 110°C | More stable than soybean/corn oil, less stable than high-oleic oils |

| Trans-fat (post-refining) | ≤ 0.3–0.5% | Small but present from high-heat deodorizing steps |

Healthier Oils and Fats to Use Instead

As you can see, none of the common seed oils stand out as genuinely health-promoting — and none have been shown to be reliably non-inflammatory when used in everyday cooking.

Whether it’s soybean, corn, sunflower, safflower, canola, cottonseed, grapeseed, rice bran, sesame, or peanut oil, each carries the same underlying problem: a high linoleic-acid load that breaks down into oxidative byproducts under heat. So what should you use instead?

While seed oils overload the body with unstable omega-6 linoleic acid, traditional fats like butter, ghee, beef tallow, lard, coconut oil, olive oil, avocado oil, and macadamia oil offer the opposite profile: they’re naturally low in PUFAs, rich in stable saturated and monounsaturated fats, and far more compatible with human metabolism.

These are the fats humans relied on for thousands of years — long before industrial seed oils appeared in the 20th century — and modern research increasingly supports their metabolic advantages.

One of the clearest demonstrations comes from the Sydney Diet Heart Study reanalysis, one of the only randomized human dietary fat trials and possibly the best clinical evidence available to us today.

In this study, replacing traditional fats with high-linoleic seed oils led to higher mortality (not statistical analysis, real deaths). Note also that cholesterol levels decrease while real deaths increased, lending more evidence that lower cholesterol levels does not improve mortality rates.

This matters because the reverse is also true: substituting seed oils with more stable fats reduces oxidative stress and improves metabolic outcomes, aligning with how the body actually responds, not just how cholesterol levels appear on paper.

More controlled human research reinforces this. In a biochemical analysis of body fat, participants who replaced seed oils with lower-PUFA fats like olive oil, butter, and animal fats saw a significant reduction in stored linoleic acid, showing that simply changing cooking fats measurably shifts the body toward a less inflammatory state.

And in a controlled clinical trial, diets rich in monounsaturated fats from oils like olive, avocado, and macadamia improved insulin sensitivity, reduced LDL oxidation, and enhanced endothelial function compared to high-PUFA seed oils — demonstrating clear metabolic advantages.

Even coconut oil, often dismissed because of its saturated fat content, outperformed soybean oil in a randomized trial, improving HDL levels and reducing abdominal fat.

And saturated-fat–rich animal fats like tallow, lard, butter, and ghee remain structurally stable under heat, producing far fewer harmful aldehydes than any seed oil — a finding supported by classic oxidation studies on cooking fats. This stability is precisely why these fats were traditionally used for frying long before the introduction of industrial vegetable oils.

The main reason people avoid these fats is fear of saturated fat — a concern rooted in outdated nutrition myths. The evidence above shows a more complicated, more interesting story: when traditional fats replace seed oils, metabolic and inflammatory markers improve, not worsen. I explore this in depth in my article “Is Saturated Fat Bad For You”, which explains why the narrative surrounding these fats is far from settled.

Across multiple high-quality human trials, the pattern is remarkably consistent: switching from seed oils to natural fats like butter, ghee, tallow, lard, coconut oil, olive oil, avocado oil, and macadamia oil leads to lower oxidative stress, improved insulin function, more stable lipids, and reduced inflammatory burden.

These fats aren’t just “safer alternatives” — they are fundamentally more stable, more nutrient-dense, and more biologically aligned with how the human body is built to function.

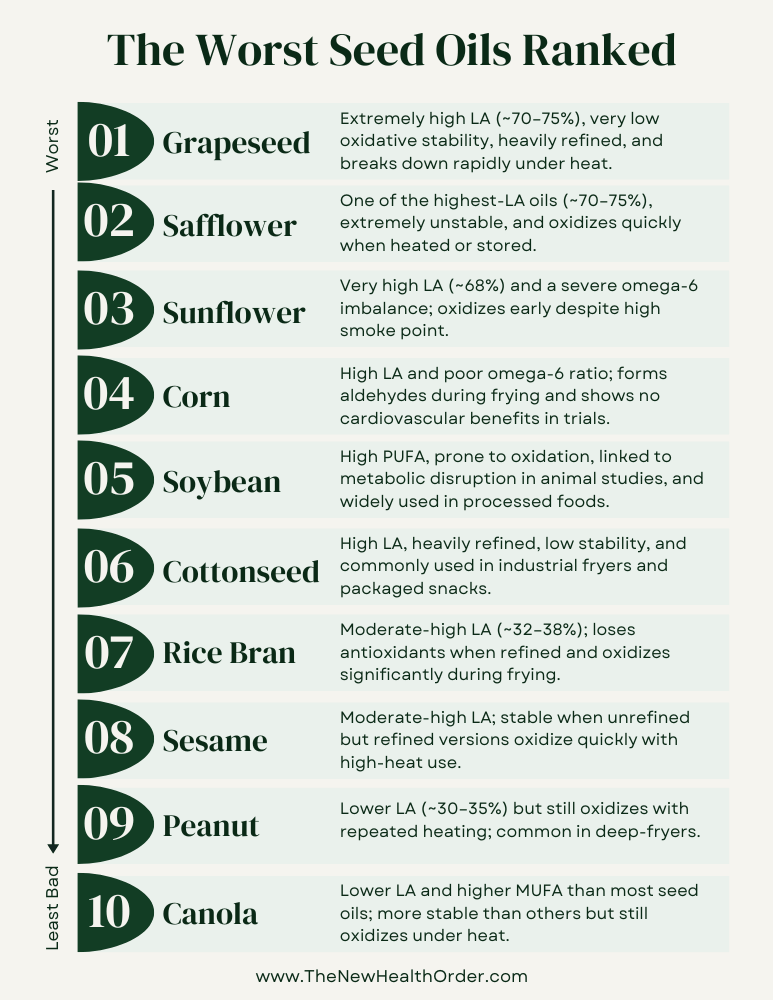

| Rank | Oil | Why It Ranks Here (Summary) |

| 1 (Worst) | Grapeseed Oil | Extremely high LA (~70–75%), very low oxidative stability, heavily refined, breaks down rapidly in high heat, among highest aldehyde formation. |

| 2 | Safflower Oil (High-LA) | One of the highest LA oils (~70–75%), extremely unstable, oxidizes rapidly when heated, poor OSI, used widely in processed foods. |

| 3 | Sunflower Oil (High-LA) | Very high LA (~68%), extremely poor omega-6 balance (~200:1), fast oxidation even before smoke point, common in packaged foods. |

| 4 | Corn Oil | High LA (~58%), very poor omega-6 ratio (~80:1), repeatedly shown to lower LDL but not improve outcomes, known to form aldehydes in fryers. |

| 5 | Soybean Oil | High PUFA (~58%), strongly linked to metabolic and inflammatory disruption in animal models, oxidizes quickly under heat, extremely widespread. |

| 6 | Cottonseed Oil | High LA (~50%), heavy industrial refining, low stability, gossypol concerns historically, widely used in deep fryers and snack foods. |

| 7 | Rice Bran Oil | Moderate-high LA (~32–38%), loses antioxidants during refining, oxidation spikes during frying, forms aldehydes similar to soybean/corn oils. |

| 8 | Sesame Oil (Refined) | Moderate-high LA (~40–45%), more stable when unrefined, but refined versions used for frying oxidize quickly; moderate risk category. |

| 9 | Peanut Oil | Lower LA than most seed oils (~30–35%), somewhat higher MUFA, but still oxidizes with high-heat and reuse; common in fryers. |

| 10 (Least Bad) | Canola Oil (Refined) | Lower LA (~20–30%), higher MUFA (~60%), better OSI than others, but still a refined seed oil that oxidizes under heat; lowest-risk but not ideal. |

Final Thoughts

Seed oils have become so common in modern food that avoiding them can feel overwhelming at first — but the science is clear enough to guide better choices. The major concern isn’t ideology or trends; it’s chemistry. Oils high in linoleic acid break down easily into reactive compounds that promote oxidative stress and inflammation, especially when heated or reused. That’s not a fringe idea — it’s a predictable biochemical outcome, supported by both mechanistic research and clinical evidence.

The good news is that you have far better options. Replacing high-PUFA seed oils with more stable, traditional fats is one of the simplest, most reliable nutrition improvements you can make. Olive oil, avocado oil, butter, ghee, coconut oil, beef tallow, lard, and macadamia oil all offer far greater heat stability, lower oxidative burden, and more favorable effects on metabolic health. You don’t need to overhaul your entire lifestyle — just swap the oils you cook with most often.

Start small:

- Choose olive oil or avocado oil for everyday cooking.

- Use butter, ghee, or tallow for sautéing and high-heat meals.

- Avoid ultra-processed foods that list soybean, corn, sunflower, safflower, cottonseed, or “vegetable oil blends.”

- Be cautious with restaurant fried foods, where oils are reheated repeatedly and oxidation is highest.

These simple changes compound quickly. By reducing your exposure to unstable seed oils and choosing fats humans have used for centuries, you lower inflammation, protect metabolic health, and support better long-term outcomes — all without counting calories or adopting a restrictive diet. Your cooking fat isn’t the whole story of health, but it’s one of the most overlooked levers you can pull. And once you’ve made the switch, you’ll never go back.