Search for “healthiest cooking oil” online and you’ll hear the same advice parotted everywhere: avoid saturated fats and choose “heart-healthy” vegetable oils.

But look past the narrative and toward modern scientific literature, biochemistry, and basic human physiology, and a very different story emerges—one that explains the growing shift away from industrial seed oils and back toward traditional, heat-stable cooking fats.

The truth is that not all oils are created equal. Some tolerate heat beautifully, remaining stable and nourishing. Others break down rapidly, producing harmful byproducts long before they reach their smoke point.

And the fats that have been demonized for decades—like butter, ghee, and tallow—And the fats that have been demonized for decades—like butter, ghee, and tallow—are naturally more stable under heat, generating fewer harmful oxidation products than seed oils.

This article cuts through the confusion and answers the real question: Which cooking oils actually support your health, and which ones should you avoid—especially when heat enters the equation?

You’ll learn which fats are the safest, most stable, and most nutrient-dense options for everyday cooking, why our recommendations differ from mainstream lists, and what the science really says about saturated fats and seed oils. By the end, you’ll know exactly which oils belong in your kitchen—and which ones don’t.

Why Our “Healthiest Cooking Oils” List Looks Different From Everyone Else’s

If you search online for the “healthiest oils,” most lists recommend canola, soybean, and other seed oils—mainly because they’re low in saturated fat. But this advice is based on decades-old assumptions that simply don’t hold up to modern evidence.

As we covered in Is Saturated Fat Bad For You? The Answer Is No!, large meta-analyses and systematic reviews now show no clear link between natural saturated fats and heart disease, undermining the primary argument used to push seed oils and discourage traditional fats like butter, ghee, and tallow.

Seed oils also come with their own set of problems: they’re extremely high in omega-6 linoleic acid, fragile under heat, and prone to forming harmful oxidative byproducts during cooking — something we explore in depth in Are Seed Oils Good For You?. By contrast, natural fats such as butter, ghee, coconut oil, olive oil, and avocado oil are far more stable, less processed, and have been part of human diets for thousands of years.

So while mainstream lists still rely on outdated cholesterol-era thinking, our recommendations reflect modern research, biochemistry, and the reality that for 99.9% of human history — long before industrial seed oils existed — rates of metabolic disease and cardiovascular problems were dramatically lower.

We also ground our choices in how different fats actually behave under real cooking conditions: their stability, oxidation potential, and biological effects. That’s why this list looks different — and why it prioritizes natural, minimally processed fats your body is biologically designed to use.

The Healthiest Oils to Cook With

Butter and Ghee

Mainstream advice still warns against butter largely because of observational studies that report tiny, statistically fragile associations—like a recent Harvard paper claiming a 15% higher mortality risk among high butter consumers. But this study (and many like it) relies on weak hazard ratios near 1.0, a level epidemiologists generally consider indistinguishable from noise or confounding.

It also grouped olive oil alongside industrial seed oils, making plant oils appear healthier by association. These are the kinds of studies that shaped decades of anti-butter guidelines, yet they’re too weak to establish cause and effect—especially compared to more rigorous metabolic, biochemical, and randomized research.

This is why we evaluate butter and ghee based on heat stability, biological function, and modern clinical evidence, rather than outdated correlation-based claims.

Butter and ghee aren’t just flavorful—they’re biochemically suited for cooking. Their heat stability, nutrient profile, and metabolic neutrality make them two of the most reliable fats in the kitchen, especially compared to fragile modern seed oils.

Exceptional Heat Stability

Butter and especially ghee handle heat far better than seed oils. Their low linoleic acid content means they don’t oxidize or form toxic byproducts during cooking. Ghee’s high smoke point of around 450–485°F (232–252°C) makes it ideal for almost any use, while butter, at around 300–350°F (150–177°C), remains stable for medium-heat uses and is excellent for low to medium-heat dishes.

This is important because many studies show that ghee and butter produce fewer oxidation products than polyunsaturated seed oils under high heat.

Meaningful Amounts of Fat-Soluble Nutrients

Butter and ghee provide real, usable amounts of vitamin A, vitamin E, and vitamin K2, especially when sourced from grass-fed animals. These nutrients support immune health, hormone production, and proper calcium metabolism.

Research shows that adequate vitamin K2 intake is associated with lower cardiovascular disease and improved bone health.

They also contain Conjugated Linoleic Acid (CLA), a fatty acid linked to improvements in body composition and metabolic health.

A Natural Source of Butyrate

Butter contains 3–4% butyrate, a rare and valuable short-chain fatty acid that supports gut integrity, reduces inflammation, and fuels colonocyte energy metabolism. Butyrate supplementation is associated with improved metabolic markers and reduced inflammation in animal and human studies.

Supported by Modern Research

Despite decades of warnings, modern evidence shows no convincing link between saturated fat and heart disease. Large meta-analyses—including:

- 2010 AJCN Meta-Analysis (21 studies, 347,000+ people)

- 2014 Annals of Internal Medicine Review

- 2020 JACC Review of Dietary Fat

—found no association between saturated fat intake and cardiovascular disease.

The PURE study, one of the largest global nutrition studies ever conducted, also found that higher saturated fat intake was associated with lower stroke risk and no increase in cardiovascular mortality.

Modern research increasingly shows that saturated fat itself is not linked to heart disease. Instead, cardiovascular risk is driven far more by factors like inflammation, metabolic health, and the presence of oxidized LDL—small, dense LDL particles that are far more prone to oxidative damage.

These harmful particles tend to rise with high-sugar, high–seed-oil diets, not with whole-food sources of saturated fat. It’s the oxidation of LDL and the resulting endothelial damage—not saturated fat—that plays a central role in the development of cardiovascular disease.

Minimal Processing

Ghee is simply butter with the water and milk proteins removed. There’s no chemical extraction, no bleaching, no deodorizing—nothing resembling the industrial processes behind modern seed oils. Butter and ghee remain whole, natural fats just as humans have consumed for thousands of years.

Enhanced Flavor

Butter and ghee naturally enhance the flavor of nutrient-dense whole foods. That’s not trivial—when food tastes better, people cook more real meals and rely less on ultra-processed snacks and takeout. Better adherence leads to better health.

Limitations

Butter has a relatively low smoke point due to its milk solids, which limits its use for high-heat cooking like searing or deep frying. Ghee solves that issue but is more expensive and may not be accessible to everyone. Both butter and ghee also carry a distinct flavor that works beautifully in many dishes but may not pair well with certain cuisines or neutral-tasting recipes.

Some individuals with dairy sensitivities can tolerate ghee, but not butter, so dietary tolerance varies.

| Property | Butter | Ghee |

| Smoke Point | 300–350°F (150–177°C) | 450–485°F (232–252°C) |

| OSI (Oxidative Stability Index) | ~5–7 hours | ~20–25 hours |

| SFA | ~50% | ~60% |

| MUFA | ~25% | ~30% |

| PUFA | ~2–3% | ~2–3% |

| Heat Stability | Good for medium heat | Excellent for high heat |

| Best Used For | Baking, sautéing, low–medium heat dishes | High-heat cooking, frying, roasting |

Beef Tallow and Lard

Beef tallow and pork lard were the primary cooking fats for most of human history, long before industrial seed oils existed. Modern research now confirms what traditional cultures already knew: these fats are exceptionally stable, chemically reliable, and well-suited for high heat.

Heat Stability and Oxidation Resistance

One of the greatest strengths of tallow and lard is their ability to withstand high temperatures without breaking down. Unlike seed oils—which are loaded with fragile omega-6 fats—tallow and lard contain very low PUFA levels and therefore resist oxidation.

Studies show that animal fats generate far fewer toxic aldehydes and oxidation products during frying than vegetable and seed oils. This makes perfect biochemical sense: saturated and monounsaturated fats have far more stable single bonds, while PUFA-rich seed oils contain multiple double bonds that are highly susceptible to heat-induced oxidation.

This makes them far safer for deep frying, searing, and repeated heating—the exact situations where seed oils become unstable and harmful.

Favorable Fat Composition for Cooking

Lard surprises many people with its composition: it is roughly 45% monounsaturated fat, similar to olive oil, and only about 11% PUFA. Beef tallow is even more saturated and therefore even more heat-stable. Research on fat oxidation consistently finds that fats with higher saturated and monounsaturated content maintain structural integrity under heat, once again due to their superior bond strengths.

In cooking terms, that means cleaner flavor, less smoke, and fewer harmful byproducts.

No Evidence of Cardiovascular Harm

There are no clinical trials showing that cooking with tallow or lard increases heart disease risk. In fact, large analyses of saturated and monounsaturated fat intake—covering hundreds of thousands of people—find no association between these fats and cardiovascular disease or mortality

The PURE Study, one of the largest global nutrition studies ever conducted, found that higher saturated fat intake was associated with lower stroke risk and had no link to heart disease Tallow and lard fall directly within the fat categories examined.

Naturally Occurring Nutrients

Pasture-raised pork fat contains meaningful amounts of vitamin D, one of the few natural dietary sources available.

Tallow and lard also contain compounds like CLA and palmitoleic acid, which have been studied for metabolic and antimicrobial effects

While not nutritional powerhouses like organ meats, they offer more useful micronutrients than nearly all seed oils.

Tallow and Lard are Traditional Fats

Unlike seed oils, which require solvents, bleaching, deodorization, and chemical refining, tallow and lard can be produced with simple rendering—nothing more. They remain whole-food fats that humans have used for thousands of years, with a track record of safety that industrial oils cannot match.

Limitations

The main limitation of tallow and lard is flavor profile—tallow has a mild beefy taste, while lard can add a slight pork essence depending on refinement. This makes them excellent for savory dishes but less ideal for delicate or neutral recipes.

Availability can also be an issue: high-quality, minimally processed versions are not always easy to find in supermarkets, and are typically expensive as a result when you do manage to find them.

| Property | Beef Tallow | Pork Lard |

| Smoke Point | ~400°F (204°C) | ~370°F (188°C) |

| OSI | ~20–22 hours | ~12–15 hours |

| SFA | ~50% | ~39% |

| MUFA | ~45% | ~45% |

| PUFA | ~3% | ~11% |

| Heat Stability | Excellent | Very Good |

| Best Used For | Frying, searing, deep frying | Roasting, baking, pan-frying |

Coconut Oil

Coconut oil is one of the most heat-stable cooking fats available, thanks to its extremely low polyunsaturated fat content and high saturation, making it far safer under heat than seed oils, which oxidize rapidly and form toxic aldehydes.

As a result, coconut oil holds its structure during frying, sautéing, and baking—a fact repeatedly shown in lipid oxidation studies.

Heat Stability

Refined coconut oil has a smoke point of around 450°F (232°C), putting it on par with ghee for high-heat applications.

Virgin coconut oil is suitable for medium-heat cooking, offering stability similar to butter. Because coconut oil contains less than 2% linoleic acid, it produces dramatically fewer harmful oxidation byproducts than seed oils during deep frying or prolonged heating.

Unique Medium-Chain Triglycerides (MCTs)

About 60% of coconut oil is composed of medium-chain triglycerides, which are absorbed and metabolized differently from long-chain fats. Studies show MCTs increase energy expenditure, enhance fat oxidation, and improve satiety

This makes coconut oil especially useful for metabolic health and ketogenic or low-carb diets.

Improves HDL and Metabolic Markers

Multiple randomized controlled trials show that coconut oil consistently raises HDL cholesterol, often outperforming olive oil. In a head-to-head RCT comparing coconut oil, olive oil, and butter, coconut oil produced the largest increase in HDL and did not significantly raise LDL.

Another trial compared coconut oil to soybean oil for 12 weeks. Coconut oil improved HDL, reduced waist circumference, and lowered inflammation, while soybean oil worsened lipid profiles.

Traditional Populations Thrive on High Coconut Intake

Anthropological studies show that populations consuming extremely high levels of coconut fat—such as the Tokelauans and Kitavans—display excellent cardiovascular and metabolic health, with no increase in heart disease despite 30–60% of calories coming from saturated fat.

Limitations

The only real limitation of coconut oil is flavor. Virgin coconut oil has a noticeable coconut aroma that works beautifully in curries, stir-fries, baking, and many Asian or Caribbean dishes, but may not suit every recipe.

Refined coconut oil, however, is virtually flavorless and ideal for high-heat cooking where a neutral fat is preferred.

| Property | Virgin Coconut Oil | Refined Coconut Oil |

| Smoke Point | ~350°F (177°C) | ~450°F (232°C) |

| OSI | ~20–24 hours | ~25–30 hours |

| SFA | ~90% | ~90% |

| MUFA | ~6% | ~6% |

| PUFA | ~1–2% | ~1–2% |

| Heat Stability | Very Good | Excellent |

| Best Used For | Medium-heat cooking, baking | High-heat frying, sautéing |

Olive Oil

Olive oil is one of the most well-studied fats in human nutrition, with decades of high-quality research showing benefits for heart health, inflammation, metabolic function, and longevity. Its strength comes from its unique combination of monounsaturated fats, polyphenols, and low omega-6 content, making it both versatile in the kitchen and supportive of overall health.

High-Quality Clinical Evidence

Olive oil is the signature fat of the Mediterranean diet, and large randomized trials have repeatedly demonstrated its benefits. The landmark PREDIMED trial—supplementing participants with 1 liter of extra-virgin olive oil per week—showed a 30% reduction in major cardiovascular events.

Meta-analyses of tens of thousands of participants also link higher olive oil intake to lower risk of cardiovascular, cancer, and neurodegenerative mortality. In one of the largest analyses to date, people who consumed just over half a tablespoon of olive oil per day had a 29% lower risk of dying from neurodegenerative disease — one of the strongest protective effects observed.

Stable for Cooking

Contrary to popular belief, extra-virgin olive oil holds up remarkably well during cooking. Its high oleic acid content and rich polyphenol levels protect it from oxidation, even under moderate heat. Studies comparing frying oils show EVOO produces far fewer toxic aldehydes than seed oils like sunflower or soybean.

Refined olive oil has a smoke point around 465°F, while extra-virgin sits in the 375–410°F range—both suitable for sautéing, roasting, and everyday pan cooking.

Rich in Anti-Inflammatory Compounds

Extra-virgin olive oil contains over 30 bioactive polyphenols, including oleuropein and hydroxytyrosol, which have documented antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects. Clinical studies show olive oil reduces oxidized LDL, supports endothelial function, and lowers inflammatory markers such as CRP and IL-6. These benefits appear whether olive oil is used raw or lightly heated.

Excellent for Both Raw and Cooked Dishes

Olive oil’s flavor and nutrient density shine when used uncooked—drizzled over salads, vegetables, soups, or grilled meats. EVOO’s polyphenols remain active even after light cooking, but raw use preserves their potency and aroma best. This dual functionality is a major reason olive oil is a staple in some of the world’s healthiest traditional diets.

Limitations of Olive Oil

Olive oil is not ideal for very high-heat applications like deep frying or searing at extreme temperatures, as its smoke point—while sufficient for most cooking—is lower than saturated fats like ghee, tallow, or refined coconut oil.

Extra-virgin olive oil can also vary significantly in quality; some commercial brands are adulterated with cheaper seed oils or undergo oxidation during storage, reducing their polyphenol content. Additionally, its distinct flavor may not suit every recipe, particularly those requiring a neutral fat.

| Property | Extra-Virgin Olive Oil | Refined (“Light”) Olive Oil |

| Smoke Point | 375–410°F (190–210°C) | ~465°F (240°C) |

| OSI | ~12–18 hours | ~18–20 hours |

| SFA | ~14% | ~14% |

| MUFA | ~73% | ~73% |

| PUFA | ~8–12% | ~8–12% |

| Heat Stability | Good–Very Good | Very Good |

| Best Used For | Sautéing, roasting, dressings | Higher-heat cooking |

Avocado Oil

Avocado oil has become one of the most popular alternatives to seed oils in recent years—and for good reason. Made from the flesh of the avocado rather than the seed, it is naturally rich in monounsaturated fats, low in omega-6, and exceptionally versatile in the kitchen. Its clean, neutral flavor makes it an easy replacement for vegetable oils in both cooking and raw applications.

Excellent Heat Stability and High Smoke Point

One of avocado oil’s main strengths is its extremely high smoke point. Refined avocado oil reaches temperatures around 480–520°F (249–271°C), making it ideal for high-heat cooking methods such as roasting, stir-frying, grilling, and even deep frying.

Its high oleic acid content—similar to olive oil—gives it strong oxidative stability under heat, producing fewer harmful breakdown products compared to seed oils.

Rich in Monounsaturated Fats

Avocado oil is composed of roughly 65–70% oleic acid, the same heart-healthy fat found in olive oil, which is associated with improved lipid profiles, reduced inflammation, and better insulin sensitivity.

Because avocado oil is low in polyunsaturated omega-6 fats, it also contributes less to dietary linoleic acid overload, making it a safer everyday cooking oil than sunflower, safflower, or soybean oil.

Supports Heart and Metabolic Health

Several randomized trials have shown that diets enriched with avocado or avocado oil improve HDL levels, lower small dense LDL particles, and reduce markers of inflammation.

While the research base is not as extensive as olive oil’s, the metabolic improvements associated with high-oleic oils generally apply to avocado oil as well.

Mild Flavor and Versatility in Both Raw and Cooked Dishes

Its neutral, buttery flavor makes avocado oil exceptionally adaptable. It works well in mayonnaise, dressings, marinades, and baking, where you need a clean-tasting fat. It also performs beautifully in high-heat cooking. This versatility sets it apart from coconut oil and some animal fats that have stronger flavor profiles.

Limitations of Avocado Oil

The biggest limitation is quality control. Multiple analyses, such as this major UC Davis study, found that over half of avocado oils on the market were either oxidized or adulterated with cheaper seed oils like soybean oil.

This significantly reduces health benefits and heat stability. Authentic, cold-pressed avocado oil also tends to be more expensive, and the taste of the unrefined versions may not be suitable for every dish.

| Property | Virgin Avocado Oil | Refined Avocado Oil |

| Smoke Point | ~375°F (190°C) | 480–520°F (249–271°C) |

| OSI | ~12–15 hours | ~15–20 hours |

| SFA | ~12% | ~12% |

| MUFA | ~70% | ~70% |

| PUFA | ~10% | ~10% |

| Heat Stability | Good | Excellent |

| Best Used For | Dressings, medium heat, marinades | High-heat cooking, grilling, frying |

What About Seed Oils?

No discussion of healthy cooking fats is complete without addressing seed oils, most commonly corn, soybean, safflower, sunflower, grapeseed, cottonseed, and the blends marketed as “vegetable oil.”

These oils dominate supermarkets and restaurants not because they’re healthy, but because they’re incredibly cheap to produce at industrial scale. Their nutritional profile and behavior under heat, however, make them a poor choice for home cooking.

Why Seed Oils Are Not Ideal for Cooking

Most seed oils are extremely high in linoleic acid (LA)—a fragile omega-6 polyunsaturated fat that oxidizes rapidly when exposed to heat, light, or air. During frying, roasting, and sautéing, these oils break down into aldehydes and lipid peroxides, compounds associated with inflammation, oxidative stress, and chronic disease.

While their smoke points may look high on paper, the real issue is chemical stability, not visible smoke. Even at modest temperatures, PUFA-rich oils degrade far faster than saturated or monounsaturated fats like ghee, tallow, coconut oil, or olive oil.

Cold Use Isn’t Much Better

Some argue seed oils are acceptable if used raw (e.g., salad dressings), but even here they fall short.

Because of their high PUFA content, they oxidize easily during storage, transport, or time on the shelf. By the time they reach your kitchen, many are already partially oxidized.

Even for cold applications, olive oil outperforms seed oils in antioxidant content, stability, and health outcomes.

Why Restaurants Use Them

It’s not because seed oils are healthy.

It’s because they’re cheap, shelf-stable, neutral in flavor, and heavily subsidized. That combination makes them perfect for large-scale food manufacturing, not necessarily for your health.

Restaurants also reuse their frying oil over and over again. PUFA-rich oils break down quickly with heat, and each reheating cycle produces even more oxidation products. It’s great for profit margins, but the science is now showing its terrible for your body.

If You Have to Use a Seed Oil…

Sometimes you need a neutral-tasting oil, or you’re limited by what’s available. In those cases, canola oil is the least harmful of the common seed oils. It’s still far from ideal, but its lower linoleic acid content makes it less prone to oxidation than soybean, corn, safflower, sunflower, or grapeseed oil.

High-oleic versions of sunflower, safflower, soybean, or canola oil are a step up from their standard counterparts. These have been bred to contain far more monounsaturated fat—often 70–80%—so they behave more like olive or avocado oil when heated.

But remember: they’re still highly refined and usually stripped of natural antioxidants, which means they don’t offer the same protective benefits as real, minimally processed oils.

See this article here for a review of the most common seed oils and their effect on health.

| Property | Standard Canola Oil | High-Oleic Seed Oils (sunflower, safflower, soybean, high-oleic canola) |

| Smoke Point | ~400°F (204°C) | ~440–450°F (226–232°C) |

| OSI (Oxidative Stability Index) | ~6–8 hours | ~12–16 hours |

| SFA | ~10% | ~10% |

| MUFA | ~60% | ~75–80% |

| PUFA | ~20% | ~3–10% |

| Heat Stability | Fair | Good |

| Best Used For | Occasional neutral-flavor cooking | Neutral high-heat cooking; better alternative to standard seed oils |

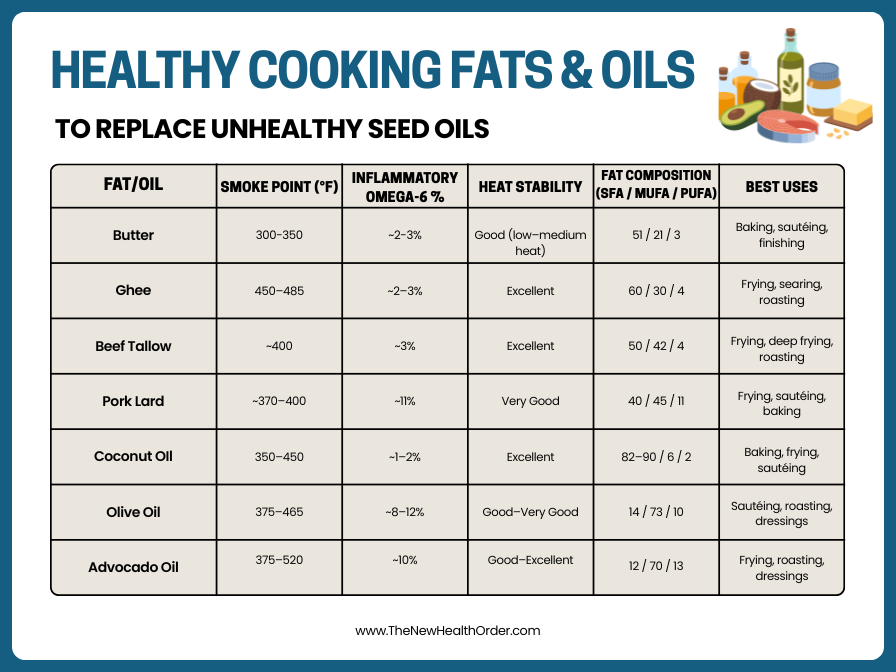

Cooking Fats & Oils Compared

| Fat / Oil | Smoke Point (°F) | Linoleic Acid (Omega-6) % | Heat Stability |

| Butter | 300–350 | ~2–3% | Good (low–medium heat) |

| Ghee | 450–485 | ~2–3% | Excellent |

| Beef Tallow | ~400 | ~3% | Excellent |

| Pork Lard | ~11% | ~11% | Very Good |

| Coconut Oil (Virgin/Refined) | 350–450 | ~1–2% | Excellent |

| Olive Oil (EVOO/Refined) | 375–465 | ~8–12% | Good–Very Good |

| Avocado Oil (Virgin/Refined) | 375–520 | ~10% | Good–Excellent |

| Canola Oil | ~400 | ~20% | Fair |

| High-Oleic Seed Oils (sunflower, safflower, etc.) | 440–450 | ~3–10% | Good |

| Standard Seed Oils (soybean, corn, grapeseed, etc.) | 420–450* | ~55–75% | Poor |

Final Thoughts

Choosing the right cooking fat isn’t about following trends or repeating old nutrition slogans; it’s about understanding how different fats behave in the real world and how they interact with your biology.

Once you look at the actual science instead of the marketing, a remarkably consistent picture emerges. The fats that humans have used for thousands of years—like butter, ghee, tallow, lard, coconut oil, olive oil, and avocado oil—are stable, resilient under heat, and rich in nutrients your body readily knows how to use. Industrial seed oils, on the other hand, are fragile, easily oxidized, and create harmful byproducts long before they reach their smoke point.

None of this means you need to be perfect or stress about every restaurant meal. Eating fires every now and again won’t kill you – the body is remarkably tough. What matters most is what you cook at home with, day after day, because that’s where the majority of your fat intake comes from.

When your everyday meals are prepared with stable, minimally processed fats, you dramatically reduce your exposure to the oxidation products that come from heating fragile seed oils. Occasional exposure outside the home becomes far less meaningful in the context of an otherwise stable nutritional environment.

A simple guiding idea is this: choose fats that can tolerate heat, that don’t oxidize easily, and that come from real foods rather than industrial extraction.

When you build your kitchen around oils and fats that are naturally stable and biochemically compatible with human physiology, you’re choosing an approach to cooking that supports better metabolic health, steadier energy, and lower inflammation.

In the end, it’s not about fear or restriction—it’s about returning to the fats that have served us well throughout human history and letting modern science confirm what tradition already knew.

FAQs

What is the healthiest oil to cook with?

The healthiest cooking oils are heat-stable fats like ghee, tallow, butter, coconut oil, and high-quality olive or avocado oil. They resist oxidation far better than seed oils.

Are seed oils bad for cooking?

Yes. Most seed oils are high in linoleic acid and oxidize quickly during heating, producing toxic aldehydes. Natural fats stay stable and are safer for high-heat cooking.

Is saturated fat unhealthy for the heart?

Modern research—including major meta-analyses—shows no clear link between saturated fat and heart disease. Oxidized LDL and inflammation pose far greater risks than saturated fat itself.