For years, we’ve been told that 600 IU of vitamin D a day is enough to keep us healthy. It’s printed on supplement labels, echoed in government guidelines, and repeated in doctors’ offices as if it were an unshakeable scientific truth. But what if that number was never correct to begin with? What if the official recommendation—followed by millions—was based on a statistical error that dramatically underestimated how much vitamin D people actually need?

In 2014, researchers uncovered exactly that. Their analysis revealed that the calculation used to set the vitamin D RDA didn’t reflect the needs of real individuals at all. And when the math was corrected, the required intake wasn’t slightly higher—it was an order of magnitude higher. Yet despite the implications for immunity, metabolic health, and long-term disease risk, the guideline has never been updated or even formally addressed.

This article walks through what went wrong, what the corrected data should actually show, and why so many people remain deficient despite following the rules. If you’ve ever wondered why your vitamin D levels stay low, even when you’re “doing everything right,” the answer starts here.

Why Vitamin D Matters More Now Than It Ever Has

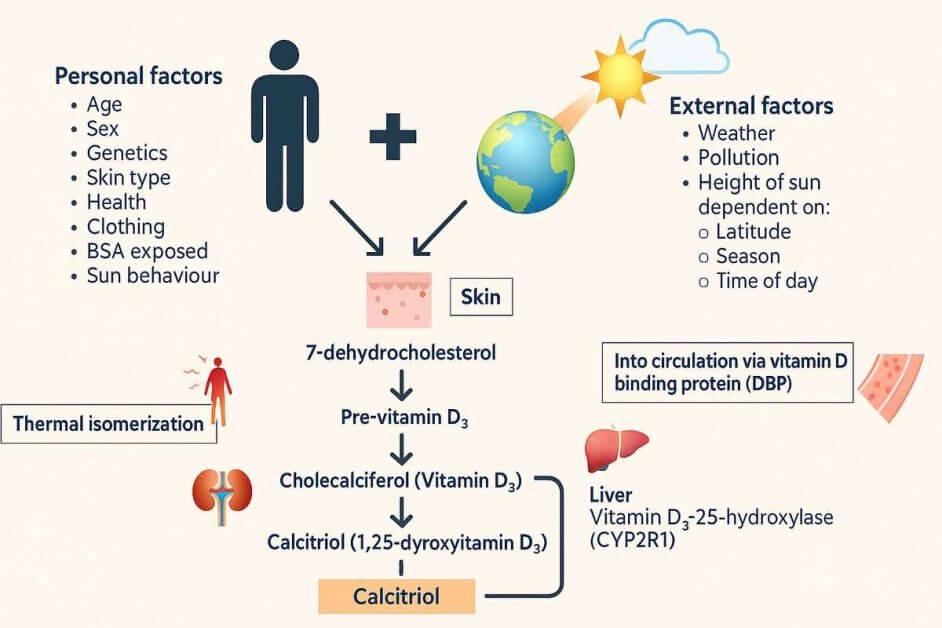

Vitamin D is involved in far more than bone health. It regulates immune responses, inflammation, metabolic function, and even the expression of hundreds of genes. When levels drop, the effects aren’t dramatic at first, but they compound. You get more frequent infections, slower recovery, and a general sense that your system isn’t firing the way it should.

Deficiency is common. Large population surveys show that roughly 25% of U.S. adults and more than one-third of Canadians fall below the 50 nmol/L mark — the threshold typically defined as deficiency. In Europe, it is closer to 40%. These numbers alone tell you that the current recommended intake is not doing its job.

One of the clearest examples is immunity. A major BMJ meta-analysis of more than 11,000 participants found that vitamin D supplementation reduced the risk of acute respiratory infections by 12%, and by 70% in those who were deficient and supplemented regularly. The key word is regularly. Vitamin D must be converted into its active form inside the body, which takes weeks, not days. By the time you get sick, it is already too late to raise your levels. This is why consistent, adequate intake matters so much.

Vitamin D also tracks closely with metabolic health. A meta-analysis of observational studies found that people with higher vitamin D levels had a 43% lower risk of developing type 2 diabetes compared with those at the bottom end of the range. Even modestly higher intake — above 500 IU per day — was associated with a measurable reduction in risk. And when you look at overall health, the pattern is similar: individuals in the lowest vitamin D category had about a 90% higher risk of all-cause mortality than those with healthy levels.

These aren’t small differences. They’re large, population-level signals pointing in the same direction: vitamin D status matters profoundly.

Which brings us to the issue at the heart of this article. If vitamin D influences immunity, metabolic health, inflammation, disease risk, and long-term survival — and if deficiency is this common — then getting the recommended intake wrong is not a trivial error.

It means millions of people are living with levels far below what their bodies actually need.

The Origin of the 600 IU Recommendation

The widely-known “600 IU per day” recommendation comes from a major 2011 report published by the Institute of Medicine (IOM), now called the National Academy of Medicine. The committee’s goal was to determine how much vitamin D the average person needed to reach a blood level of 50 nmol/L—a threshold chosen because it is believed to reliably prevent rickets and severe bone disease.

Importantly, 50 nmol/L was not selected as a marker of optimal health, immune strength, or metabolic wellbeing. It was simply the minimal level associated with preventing obvious skeletal deformities.

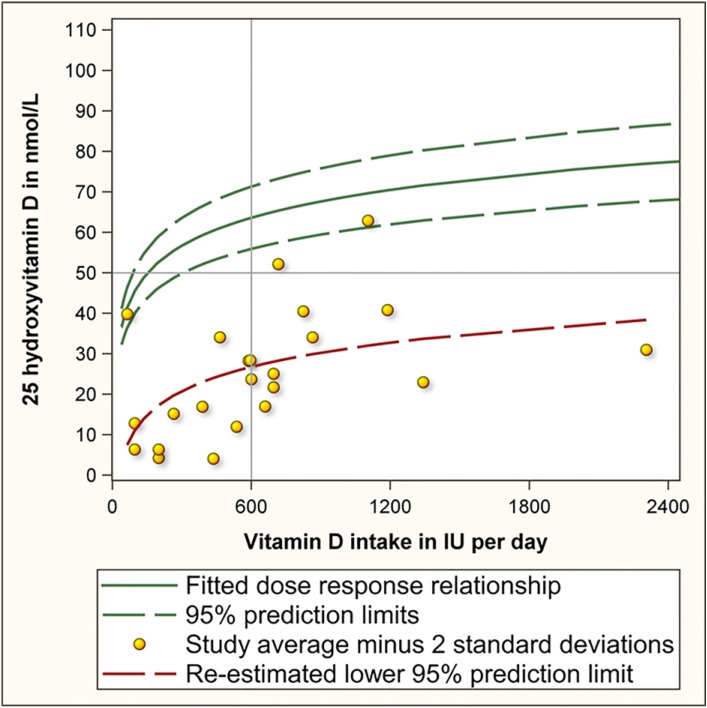

The IOM gathered ten vitamin D supplementation studies conducted during winter in high-latitude regions, where sunlight is too weak to produce meaningful vitamin D. These studies produced thirty-two group-average data points showing how different daily doses of vitamin D affected blood levels.

From these dose–response averages, the IOM calculated that 600 IU per day would allow almost everyone to reach at least 50 nmol/L. That number eventually became the Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) used in the U.S. and Canada. The United Kingdom mirrored the same approach but rounded down to 400 IU, creating an even lower national recommendation.

While 50 nmol/L may be enough to prevent rickets, it is not a target associated with thriving. A growing body of research shows that immune function, metabolic health, and mood regulation improve at significantly higher levels. For example, several large observational studies show protections against respiratory infections and chronic disease occurring around 75–100 nmol/L rather than 50.

Traditional, outdoor-living populations help illustrate this point. Groups such as the Maasai and Hadza in East Africa routinely exhibit natural vitamin D levels in the 100–150 nmol/L range, without supplements and without signs of toxicity. These levels are not accidental—they’re the physiological result of regular sun exposure and a lifestyle closer to what humans evolved with.

For a deeper look at how sunlight and supplements differ—and why your body handles them in completely different ways—see my article Vitamin D: Sunlight vs Supplements — What You Really Need.

By contrast, modern indoor living leaves most people with levels far below even the modest 50 nmol/L target. Many national surveys show that 25–40 percent of adults fall into the deficient range, suggesting that the current recommended intake is not enough to meet even the IOM’s original, minimal intent.

This context is important, because the next section will explore whether the method used to justify the 600 IU recommendation actually achieved what the IOM believed it did.

What Different Vitamin D Levels Mean

| 25(OH)D Level | nmol/L | What Research Shows |

| Severe deficiency | <30 | High infection & disease risk |

| Deficiency | 30–50 | Minimal bone protection only |

| “Adequate” (IOM) | 50 | Prevents rickets, nothing more |

| Optimal | 75–100 | Better immunity, metabolic health |

| Ancestral range | 100–150 | Seen in Maasai/Hadza without toxicity |

The Problem: A Statistical Error Hidden in the Guidelines

When the Institute of Medicine created the 600 IU per day guideline, the intention was reasonable enough. The RDA is supposed to reflect the amount of vitamin D needed so that 97.5 percent of individuals reach a minimum blood level—in this case, 50 nmol/L. It is not meant to represent what the “average” person requires. It is meant to cover almost everyone, including those who naturally absorb or convert vitamin D less efficiently.

The issue is that the IOM never actually calculated what 97.5 percent of people needed. Instead, they calculated the dose required for 97.5 percent of the study averages to reach the target. This distinction sounds small on paper, but it fundamentally alters the outcome.

Averages hide variability. Imagine a classroom where the average exam score is 80 percent. That does not mean every student scored 80. Some may have scored 95, while others barely passed—or failed. If you judged the whole class by the average alone, you’d miss the individuals who needed extra support. Vitamin D studies work the same way. When you only look at the average blood response for each dosing group, the people who respond poorly are effectively erased from the calculation.

That’s precisely what happened here. By using the group averages from each supplementation study, the IOM unintentionally smoothed away the natural spread of individual responses. The “slow responders”—the people who need more vitamin D to achieve the same blood level—disappeared inside the averages. When that variability is lost, the required dose begins to look much lower than it really is for real individuals living in the real world.

This matters because the RDA is supposed to protect nearly everyone, not a theoretical “average study group.” The moment individual variability is removed, the calculation stops fulfilling its purpose. The recommendation that emerges may look adequate on paper, but it no longer reflects the biological reality of a diverse population with very different vitamin D needs.

What the Correct Calculation Shows

When researchers went back to the original supplementation studies and analyzed the data the way the RDA is actually defined—by looking at individual variation rather than study averages—the picture changed dramatically.

The question they asked was simple:

“If we look at real people instead of averages, how much vitamin D does it take for 97.5 percent of individuals to reach at least 50 nmol/L?”

This time, instead of smoothing everyone into a single group value, the full spread of human responses was included. Some people’s vitamin D levels rise quickly with supplementation. Others barely move at all. When that variability is accounted for, the dose needed to cover almost everyone becomes much clearer.

The corrected analysis showed that a daily intake of 600 IU does not bring nearly all individuals to 50 nmol/L. In fact, it falls far short. When individual-level variation was applied to the same data, researchers found that 600 IU per day would leave a large portion of the population still below the minimum target. A dose that looked “sufficient” on paper suddenly became inadequate when viewed through the lens of real human biology.

So what would the correct number be?

When the data were recalculated properly—using the actual range of individual responses—the estimated intake needed to bring 97.5 percent of people above 50 nmol/L was roughly:

≈ 8,900 IU per day.

This figure is not meant to be a universal prescription. It is a mathematical illustration of how far the original estimate missed the mark. If the intended goal was to ensure that almost everyone reached the minimum threshold for preventing rickets and basic bone disease, then the dose required appears to be an order of magnitude larger than what was recommended.

And this is before we even ask whether 50 nmol/L is high enough for modern health needs.

Why 50 nmol/L Is Barely the Minimum

The entire foundation of the 600 IU recommendation rests on the assumption that a blood level of 50 nmol/L is enough. But this threshold was chosen for one very narrow purpose: it’s the level at which the risk of rickets and bone deformities becomes extremely low. It represents the point where bones don’t visibly fail—not the point where immune function, metabolism, or long-term health operate at their best.

Over the past two decades, research has shown repeatedly that many of vitamin D’s most important physiological effects occur well above the 50 nmol/L line.

Immune health is the clearest example. A major individual-participant meta-analysis published in the BMJ (over 11,000 participants) found that vitamin D supplementation reduced the risk of acute respiratory infections, with the strongest effects seen when levels were raised consistently and when deficiency was corrected. Benefits were most pronounced at levels above 75 nmol/L, not at the minimum threshold.

Metabolic outcomes follow a similar pattern. A systematic review and meta-analysis found that people with higher vitamin D levels had a significantly lower risk of developing type 2 diabetes, with the steepest risk reduction occurring as individuals moved out of deficiency and toward 75 nmol/L or higher.

When researchers examine broader health outcomes, the trend remains the same. A large meta-analysis in the BMJ, pooling data from 32 cohort studies, found that individuals in the lowest vitamin D category (roughly 0–22 nmol/L) had a 90 percent higher risk of all-cause mortality than those with healthy levels, and the lowest mortality risk clustered well above the 50 nmol/L line.

If we look at traditional populations, the contrast is even more striking. Groups such as the Maasai and Hadza, who live largely outdoors and eat nutrient-dense ancestral diets, routinely exhibit natural vitamin D levels between 100 and 150 nmol/L—without supplements and without signs of toxicity. These levels likely reflect the physiological environment humans evolved in, especially lots of exposure to sunlight.

Placed side by side, the gap becomes obvious. 50 nmol/L is a survival threshold, not a thriving threshold. It keeps rickets away, but it sits well below the levels associated with resilient immunity, lower chronic disease risk, and better long-term health outcomes.

And if the minimum itself is set too low, any intake recommendation based on that number—especially one weakened by a statistical error—will inevitably fall short for a large share of the population.

Thriving appears to happen in a very different part of the vitamin D spectrum.

So How Much Vitamin D Do You Actually Need Per Day?

After seeing how far the original 600 IU recommendation missed the mark, the next question is the one everyone really cares about: how much vitamin D do you actually need each day to maintain healthy levels?

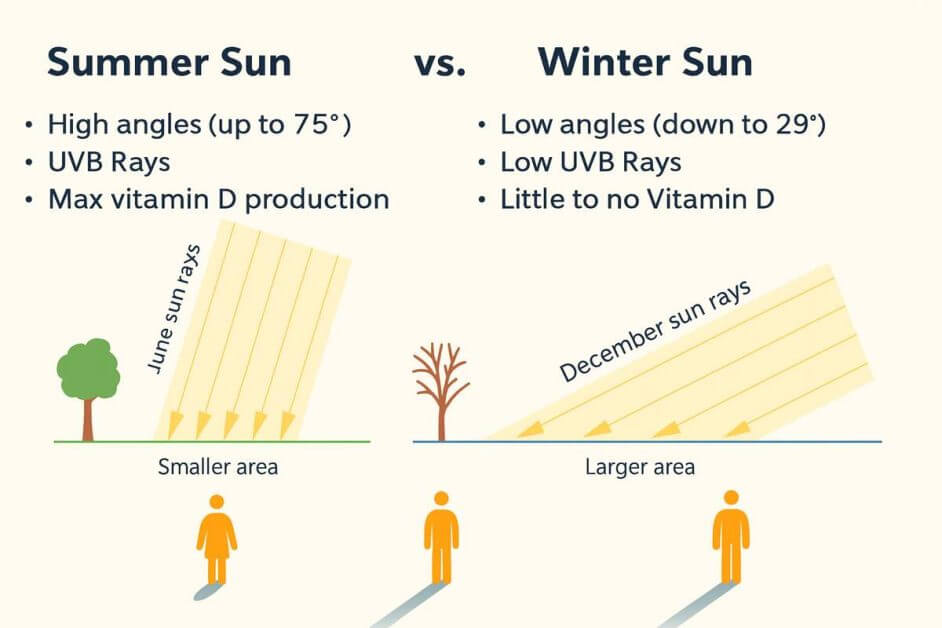

There isn’t a single perfect answer, because people absorb and convert vitamin D very differently. Body weight, skin pigmentation, latitude, season, age, and time spent outdoors all influence how your blood levels respond.

What’s more, studies show that vitamin D toxicity (i.e., taking too much vitamin D) is a real problem, although the number at which this occurs varies widely and is extremely controversial. Official limits state an upper limit of around 4000 IUs daily, while others claim to take 10,000 IUs daily with no adverse effect. For what it’s worth, I have been taking 8000 IUs supplementation daily with no noticeable adverse effects, although this is not a recommendation for you.

What the corrected calculation shows, however, is that the official recommendation was never designed to meet real biological needs. It was designed to meet a mathematical threshold using a flawed method. When also taking into account that fact that 75 – 100 nmol/L have been shown to be better for optimal health then the basic 50 nmol/L recommended by professional bodies, its clear that reaching those ranges in a modern indoor lifestyle usually requires more than the token 400–600 IU found in multivitamins or government guidelines.

Clinical experience and supplementation studies suggest that many adults need somewhere between 2,000 and 4,000 IU per day just to reach mid-normal levels. Others—particularly those with darker skin, higher body fat, limited sun exposure, or absorption issues—sometimes require 4,000 to 6,000 IU per day or even more. This isn’t unusual; it’s simply a reflection of human variation, the very thing the original calculation failed to account for.

Modern Vitamin D Inputs vs Ancestral Inputs

| Source | Estimated Daily IU Equivalent | Notes |

| Indoor lifestyle | 100–300 IU | Barely moves blood levels |

| Casual sun | 1,000–4,000 IU | Arms/face only |

| Midday full-body sun | 10,000–20,000 IU | Natural, self-regulated |

| Typical supplements | 400–800 IU | Often insufficient |

| Effective range for many adults | 2,000–4,000 IU | Varies by individual |

The corrected statistical model showed something else as well: if you were to guarantee that 97.5 percent of people reach even the minimum threshold of 50 nmol/L, you would need to model a daily intake close to 8,900 IU.

That number isn’t meant to be a recommendation. It’s a mathematical demonstration of how far the original estimate was from reality. But it does tell us something meaningful: vitamin D requirements are far higher and far more variable than the official guidance suggests.

So how should you think about your own intake? The most practical approach is to focus on your blood level, not a generic dose. A simple 25(OH)D test—available through your doctor, a walk-in lab, or an at-home finger-prick kit—will tell you exactly where you stand. Supplement consistently, then retest after several weeks to see how your body responds and adjust your intake as needed. The goal isn’t to hit a specific IU number; it’s to reach and maintain a level where your immune system, metabolism, and overall physiology operate smoothly.

The right daily intake will look different for everyone, but the evidence is unmistakable: for most adults living modern indoor lives, 600 IU per day is not enough, and it was never enough. The question is not whether you need more—it’s how much more your body personally requires to reach and remain in a healthy range.

Why the Guidelines Were Never Corrected

The statistical error behind the 600 IU recommendation wasn’t discovered last year—it was published publicly in 2014. That means more than a decade has passed with no correction, no revision, and not even an official acknowledgment from the agencies responsible for setting vitamin D policy. Given how widely vitamin D deficiency affects immunity, metabolic health, and long-term disease risk, this silence is difficult to justify.

Updating public guidelines is complex, but complexity alone is not enough to explain a decade of inaction. At minimum, one would expect a formal review, a public statement, or an interim advisory while the evidence was re-evaluated. None of that happened. The corrected analysis was not refuted. It was simply absorbed into academic literature while the original, incorrect recommendation continued to shape national nutrition policy.

To try to be fair, part of the issue is institutional inertia. Once a value becomes codified as an RDA, it becomes embedded in food fortification policies, supplement regulations, clinical practice, and public health messaging. Changing it would require coordinated shifts across multiple systems.

But difficulty is not an excuse. Not when public health is at stake. When the underlying math of a public health guideline is demonstrated to be flawed, the responsible agencies have an obligation to review it—especially when the error leads to a recommendation that may leave millions of people below even the minimal threshold for basic health.

Despite the flaw first being discovered in 2014, the vitamin D debate only resurfaced intro mainstream domain during the COVID era, when viral respiratory illnesses became a global focus and people began scrutinizing their immune health more closely.

We have already seen how vitamin D has long been supported by strong evidence showing reduced risk and severity of acute respiratory infections — demonstrated well before COVID by large meta-analyses such as the 2017 BMJ study we saw earlier.

Yet during the pandemic, this evidence was often dismissed or labeled as “misinformation.” Several rapid COVID-specific studies were poorly designed, under-dosed participants, or measured vitamin D too late in the illness, leading to predictable null results.

These limitations were widely overlooked in public messaging, creating the impression that vitamin D was ineffective, even though the studies did not meaningfully test vitamin D’s protective role in the first place. The result was a confusing public narrative: a nutrient with a well-documented role in respiratory immunity was treated as controversial precisely when people needed clarity most.

At the same time, millions of individuals began testing their vitamin D levels and discovered they were deficient even while taking the officially recommended 600–800 IU per day. This mismatch—combined with renewed attention on immune health—drew fresh scrutiny to the decade-old statistical error in the vitamin D RDA. A paper quietly published in 2014 suddenly made sense of a problem people were experiencing firsthand.

Despite the correction being published more than a decade ago, the original IOM report—and the flawed RDA it produced—has never been formally revisited. In the meantime, millions of people continue to fall below even the minimal vitamin D threshold, experiencing avoidable infections, weaker immunity, and health issues that could be mitigated with adequate levels.

Improving vitamin D status remains one of the simplest, safest, and most cost-effective ways to support population health, yet the silence from major health institutions has been striking. It is difficult not to question why a mistake of this magnitude has gone unaddressed for so long.

FAQs

Is 600 IU of vitamin D enough?

No. The original RDA was based on a statistical error. For many people, 600 IU is not enough to reach even minimal healthy blood levels.

How much vitamin D per day do most adults actually need?

Most adults require more than the 600 IU guideline. Many adults need a minimum of 50 nmol/L, ideally closer to 75 nmol/L, which may require vitamin D supplementation of upwards of 4000 IUs a day.

What blood level of vitamin D should I aim for?

Research suggests that immune and metabolic benefits appear around 75–100 nmol/L, which is well above the minimal 50 nmol/L threshold used in the original RDA calculation.