“How many carbs do you need per day?” is a question most people assume already has a settled scientific answer. In reality, it doesn’t – at least not in the way it’s usually presented.

Carbohydrates are often treated as a dietary requirement and the foundation of a healthy diet, yet human physiology tells a more nuanced story. The body requires glucose, but it does not require dietary carbohydrates to obtain it. Understanding that distinction changes how carbohydrate intake should be evaluated.

In this article, we’ll examine what carbohydrates actually do in the body, where modern carbohydrate recommendations came from, and why they were never based on a demonstrated biological requirement. You’ll learn how the body maintains glucose levels without eating carbs, what happens when carbohydrate intake stays high, and why some people thrive when carbs are dramatically reduced, and even eliminated.

The goal is not to tell you what to eat, but to give you the biological context needed to make an informed decision. By the end, you’ll understand whether carbohydrates are serving a purpose in your diet, or simply occupying space by default.

What Are Carbs?

Carbohydrates are one of the three macronutrients, alongside fat and protein. At a basic level, they are compounds made of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen that the body can break down into glucose.

Carbs fall into three broad categories:

- Sugars, which are rapidly absorbed and quickly raise blood glucose

- Starches, which are chains of glucose that are broken down during digestion

- Fiber, which is technically a carbohydrate but does not meaningfully raise blood glucose

When people talk about “carbs” in a nutritional context, they are almost always referring to the glucose-producing forms – sugars and starches.

Fiber is a bit of a different subject, but you can explore it more in this article here.

For a full overview of exactly what carbs are, and how they affect your body, see this article here.

What Happens When You Eat Carbs?

When consumed, digestible carbohydrates (sugars and starches) are broken down into glucose, which enters the bloodstream. In response, the pancreas releases insulin, a hormone that helps move glucose into cells where it can be used for energy or stored for later use if it senses more glucose than the body can use right now (see this article here for a thorogh look at insulin and its importance in metabolic health).

This process is normal human physiology. Glucose and insulin are not inherently harmful. Problems tend to arise when this glucose-based pathway becomes chronically dominant, rather than one of several flexible energy options.

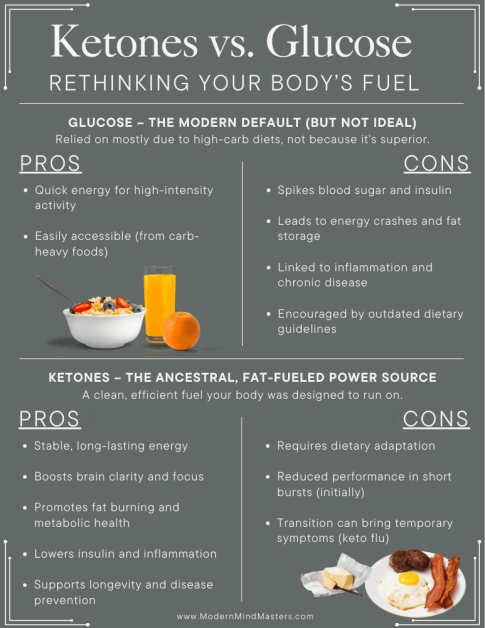

As a result, many people remain in a near-continuous state of glucose-dominant metabolism. The body is rarely required to transition to its alternative fuel system (fat-derived ketones) and over time, the ability to switch smoothly between fuel sources deteriorates.

For many, this glucose-locked state persists for years or even decades. This loss of metabolic flexibility is where the real problem with carbohydrates begins.

Are Carbs Essential?

In nutrition, the word essential has a specific meaning. An essential nutrient is one that the body cannot produce in sufficient quantities and must therefore be obtained from the diet. A true dietary requirement is one whose absence leads to a predictable deficiency and functional impairment.

By that definition, carbohydrates are not essential. Unlike amino acids, fatty acids, vitamins, and minerals – all of which have clearly defined dietary requirements – there is no nutrient class called “essential carbohydrates.” Put another way, if you do not consume carbohydrates, the body would not be deficient in any essential molecule.

Essential vs Non-Essential Nutrients

| Nutrient Type | Essential? | Reason |

| Amino acids (some) | Yes | Cannot be synthesized |

| Fatty acids (omega-3, omega-6) | Yes | Cannot be synthesized |

| Vitamins & minerals | Yes | Required for function |

| Carbohydrates | No | Glucose can be produced internally |

Glucose Is Essential. Dietary Carbohydrates Are Not

Glucose itself is essential. Certain tissues rely on it, and the body works hard to keep blood glucose within a narrow, stable range. What’s often missed, though, is that this doesn’t mean glucose has to come from the carbohydrates you eat.

Dietary carbs are simply one way to supply glucose. When carb intake is low (or even zero) the body makes the glucose it needs on its own through glycogen breakdown and gluconeogenesis. This isn’t an emergency workaround. It’s a normal, built-in part of human physiology.

When carbohydrates are available, the body will usually use that glucose first. But that “preference” is really about convenience and availability, not because glucose is a superior fuel or because the body can’t function without dietary carbs. When glucose from food isn’t coming in, fat and ketones naturally step in and take on a larger share of the workload, without compromising glucose-dependent processes.

So the distinction is simple, but significant: glucose is required – dietary carbohydrates are not.

Dietary Carbs Changes Glucose Regulation

Dietary carbohydrates bring glucose into the system from the outside. Instead of being produced internally when it’s actually needed, glucose shows up in fixed amounts based on what you eat, how much you eat, and how often you eat.

Because of that, blood sugar regulation becomes more reactive. Insulin has to rise to deal with incoming glucose whether the body was asking for it or not. This is something the body can handle – but handling a constant supply of external glucose isn’t the same as being designed to rely on it.

When carbohydrates are eaten frequently, glucose is almost never absent long enough for the body to switch over to its other fuel systems. Fat and ketones are used less, not because they’re unnecessary, but because glucose is always available. Over time, this reduces metabolic flexibility and reinforces a state of glucose dominance by default.

Where Do Daily Carbohydrate Recommendations Come From?

Daily carbohydrate recommendations are often assumed to reflect a biological requirement, but that is not how they originated.

Carbohydrates were never identified as an essential nutrient in the way vitamins, minerals, essential fatty acids, or amino acids were. There is no known carbohydrate deficiency disease, and this has been acknowledged for decades in human physiology research, including classic work on fasting metabolism showing that glucose can be produced internally when dietary intake is low.

Despite this, carbohydrates gradually became the default foundation of modern dietary advice.

When Numbers First Appeared

The first widely cited numeric carbohydrate recommendations came from the Institute of Medicine (IOM) in the early 2000s, through its Dietary Reference Intakes report. This report introduced both a Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) of 130 grams per day, and an Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Range (AMDR) of 45–65% of total calories.

Importantly, the IOM report itself notes that this carbohydrate intake was not based on a demonstrated dietary requirement. The 130g figure was derived from estimates of average brain glucose use in people already eating high-carbohydrate diets, with an added safety margin – not from evidence that lower intakes cause harm. The report also acknowledges that glucose can be supplied endogenously via gluconeogenesis.

Importantly, the report stated that the brain utilizes roughly 130g of glucose per day, but it did not claim that this glucose must come from dietary carbohydrates – a distinction the original authors acknowledged, but one that has largely been lost in public messaging.

It is also well established that the brain’s glucose requirement drops substantially when ketones are available as an alternative fuel, falling to roughly 40–50 g per day in a ketogenic state. This adaptive shift has been documented for decades and is explored in more detail in my full article on the ketogenic diet.

In other words, the numbers reflect assumed needs when running only on glucose, not a biological minimum.

Why Carbs Became the Default

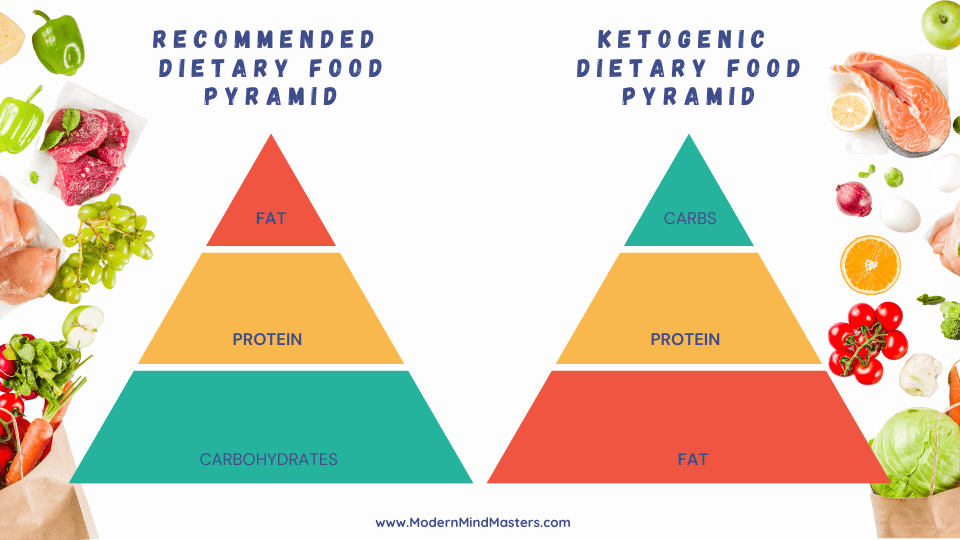

Long before carbohydrates were assigned formal intake ranges, they were already positioned as the base of the diet through food policy and public guidance.

As nutrition advice shifted toward low-fat recommendations in the mid-20th century, carbohydrates were promoted largely as a replacement calorie source.

The misguided move toward low-fat dietary guidance had predictable consequences. With fat discouraged and protein intake effectively capped, carbohydrates were left to fill the remaining caloric gap.

Viewed through the lens of higher-quality evidence and mechanistic research, this reduction of dietary fat was not supported by sound science. I examine that evidence, and its implications for metabolic health, in more detail in my article: Is Saturated Fat Bad For You?

This trend toward higher carbohydrate consumption was reinforced by U.S. dietary guidelines beginning in 1980 and visually cemented by the 1992 Food Guide Pyramid, which placed grains and starches at the base of the diet.

These recommendations were shaped mainly by population modeling and epidemiology, not controlled trials demonstrating a minimum carb requirement. They were not based on experiments demonstrating that high carbohydrate intake is required for metabolic health. Primarily because there are none.

Recommendation vs Requirement

A recommended intake is not the same as a required intake.

Vitamin C, for example, has a clearly defined dietary requirement because its absence produces a specific, reproducible deficiency disease: scurvy. Controlled observations showed that intakes below a certain threshold reliably led to connective tissue failure, while modest supplementation prevented it. The recommended intake was therefore anchored to demonstrated deficiency prevention, not population averages.

Even when guidelines try to define requirements (e.g., vitamin D), errors can occur — I break down the statistical mistake behind the current vitamin D targets here.

Carbohydrate recommendations, however, do not follow this model at all.

There is no deficiency disease caused by low carbohydrate intake. No intake threshold below which human physiology fails. And no experimental evidence demonstrating that a minimum amount of dietary carbohydrate is required for health. Instead, carbohydrate targets were inferred from estimated glucose use in carbohydrate-fed individuals and then scaled to fit an already carbohydrate-dominant diet.

This difference matters. Nutrients like vitamin C and vitamin D were recommended because their absence caused harm. Carbohydrates were recommended because they were already present and because other macronutrients were being actively reduced.

How the Body Gets Glucose Without Eating Carbs

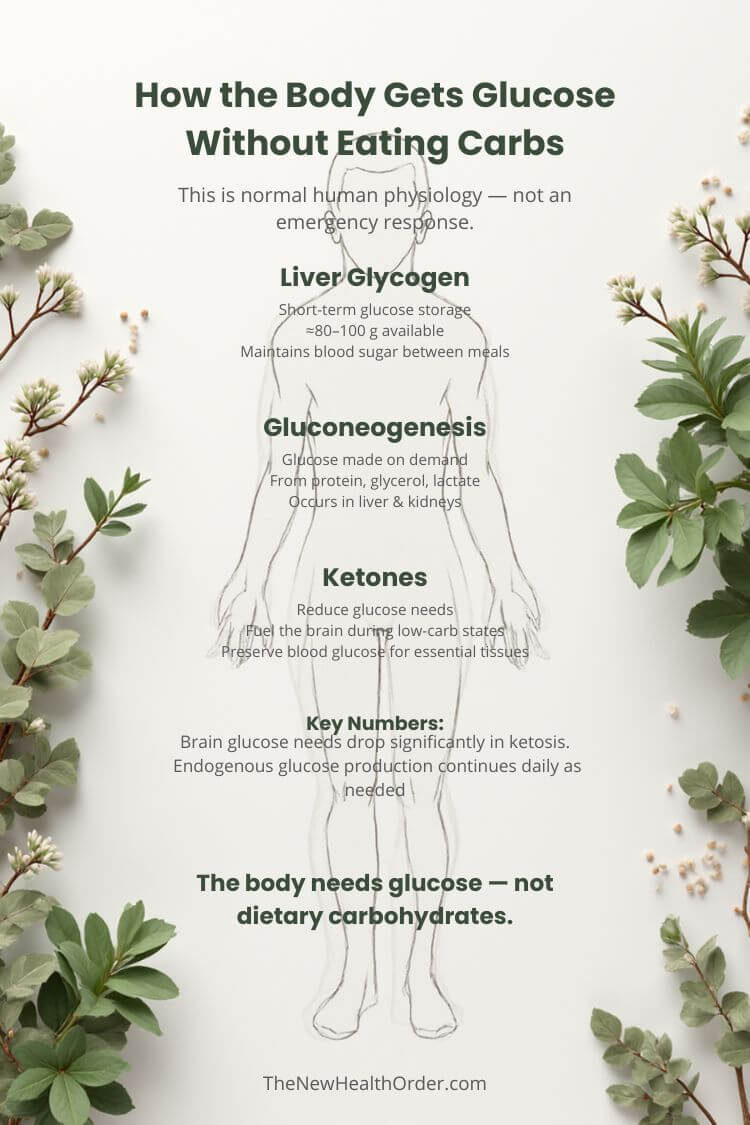

Because glucose is essential for many functions, the body has multiple built-in systems to ensure a steady supply, even when no carbohydrates are eaten at all. These systems are not emergency backups; they are fundamental aspects of human metabolism.

Glycogen: Short-Term Glucose Storage

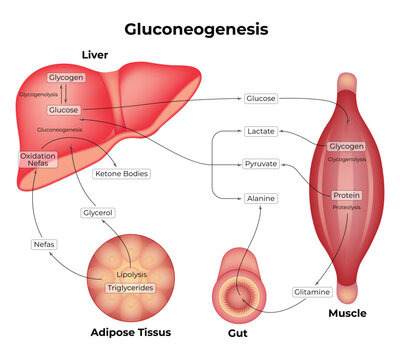

After meals, excess glucose is stored as glycogen, primarily in the liver and skeletal muscle. Liver glycogen (≈80–100 g) helps maintain blood glucose between meals and overnight, while muscle glycogen (≈300–500 g) is reserved for local muscle use and cannot be released into the bloodstream.

Importantly, liver glycogen is not replenished only by dietary carbohydrates. Even in the absence of carbs, the liver can rebuild glycogen using glucose produced internally from protein and fat via gluconeogenesis. In other words, eating meat and fat does not prevent glycogen maintenance – it simply shifts how that glucose is supplied.

When dietary glucose intake falls, liver glycogen is broken down to keep blood sugar within a narrow, tightly regulated range. In most people, these stores can support blood glucose for roughly 12–24 hours, depending on activity level and metabolic state.

This mechanism alone explains why short-term carbohydrate absence does not lead to hypoglycemia in healthy individuals.

Crucially, gluconeogenesis is demand-driven, not diet-driven. The body increases glucose production when it is needed and suppresses it when it is not. This system has been extensively documented in both fasting and low-carbohydrate conditions, including classic metabolic studies by Cahill and colleagues.

Ketones Reduce Glucose Needs

During prolonged carbohydrate restriction, the body increases the production of ketone bodies from fat. These ketones supply a large portion of the brain’s energy needs, which significantly reduces (but does not eliminate) glucose demand.

In a carbohydrate-fed state, the brain may utilize ~120 g of glucose per day. In nutritional ketosis, brain glucose requirements drop substantially, often to around 40–50 g per day, with the remainder supplied by ketones. This shift has been demonstrated in human fasting and ketogenic diet studies dating back decades.

The remaining glucose requirement is readily met through gluconeogenesis.

Carbs are Supplementary, Not Standard

For most of human history, carbohydrates were not a constant, reliable part of the diet. Fruits were seasonal, starchy plants were limited by geography and effort, and concentrated sugar sources were rare. That meant glucose was valuable when it appeared – but it wasn’t always available.

As a result, human metabolism evolved with fat and ketones as the default, steady-state fuel, and glucose as a useful, opportunistic add-on. When carbohydrates showed up, the body could take advantage of them quickly. When they disappeared, metabolism shifted back to fat and ketones without issue.

This doesn’t mean glucose metabolism is harmful or unnatural – it simply means it was never meant to dominate all the time. Ketosis isn’t an emergency state; it’s the background state that allows the system to keep running when carbohydrates aren’t on the table. When carbohydrates are found, the body will process them and gladly make use of the extra energy, but then return back to its background ketogenic state.

So, How Many Carbs Do You Need Per Day?

If we strip away habit, culture, and food politics and look only at human biology, the answer is surprisingly simple: you don’t need any dietary carbohydrate to survive or maintain basic metabolic health.

From a metabolic standpoint, the minimum required intake of dietary carbohydrate is 0 grams per day. That statement often sounds more extreme than it is, largely because glucose and dietary carbohydrates are frequently treated as the same thing when they are not.

The body does require glucose for certain tissues and processes. What it does not require is that this glucose comes from carbohydrates in the diet. When carbohydrate intake is low or absent, glucose is produced internally through gluconeogenesis, and this production continues even during prolonged fasting. At the same time, ketones take over much of the brain’s energy demand, significantly reducing the need for glucose.

This is why there is no recognized carbohydrate deficiency disease. There is no equivalent of scurvy for carbs, and no documented intake below which human physiology fails, provided protein and fat needs are met.

None of this means that eating carbohydrates is inherently harmful, or that you must avoid them entirely. It simply means that carbohydrates are optional, not required. From a long-term metabolic health perspective, the body loses nothing essential by not eating them – and often gains stability instead. Lower insulin levels, fewer glucose swings, and more time spent in a fat- and ketone-dominant state are common outcomes.

How many carbohydrates you choose to eat is therefore a matter of trade-offs: metabolic health, performance demands, lifestyle, and how much time you allow your body to spend away from glucose dominance.

The more meaningful question isn’t how many grams of carbs appear on a nutrition label. It’s whether you’re giving your body enough time away from constant glucose availability to recover, burn fat, and function on its default fuel system.

Factors that Influence Carb Tolerance

Even though the minimum requirement is zero, not everyone will do the same thing with that information. People clearly differ in how many carbs they can include without getting into trouble.

A few major factors shape that tolerance:

1. Metabolic health and insulin sensitivity

Someone with excellent insulin sensitivity, stable blood sugar, and no signs of metabolic syndrome can usually handle more carbs with less obvious downside. Someone who is insulin resistant, prediabetic, or diabetic may see blood sugar and insulin spikes from the same intake.

2. Activity level and training type

High-intensity or glycolytic training (sprints, CrossFit, repeated hard efforts) uses more glucose. In that context, carbs can be used more efficiently and sometimes strategically. For low-intensity, walking, lifting, and most daily life, fat and ketones more than suffice.

3. Muscle mass

Muscle is a major glucose sink. The more lean mass you carry, the more room you have to store and use carbs without huge blood glucose excursions. That doesn’t turn carbs into a health requirement, but it does change how forgiving your body is.

4. Meal frequency and pattern

Even the same total daily carb intake behaves differently depending on whether it’s eaten in constant grazing vs. a couple of distinct meals. Constant snacking keeps insulin elevated and makes it harder to ever reach a true fat- and ketone-dominant state.

Why Many Thrive on Low-Carb Intakes

For some people, very low-carb intake doesn’t just “work” – it meaningfully improves how the body functions day to day.

Spending more time in nutritional ketosis shifts metabolism away from constant glucose processing and toward fat and ketones as primary fuels. In this state, insulin levels remain consistently low, which reduces the need for repeated insulin spikes and makes stored fat easier to access. Blood glucose tends to stabilize, energy fluctuations smooth out, and appetite regulation often improves without deliberate restriction.

Extended time in ketosis also appears to support deeper cellular maintenance processes. Lower insulin and reduced glucose availability are associated with increased autophagy, lower oxidative stress, and reduced baseline inflammation – all factors linked to long-term metabolic and cellular health. While these effects are not exclusive to ketosis, ketosis makes them easier to sustain without continuous calorie restriction.

Another often overlooked benefit is metabolic calm. When the body is no longer swinging between glucose highs and lows, hormonal signaling becomes steadier. Many people report clearer thinking, more consistent energy, and fewer inflammatory or mood-related symptoms once fully adapted.

In our own experience, this pattern holds. My family and I have eaten fewer than 20 grams of carbohydrates per day for around a year. Our blood markers are excellent, body weight is stable and optimal, and we report good overall health with no adverse effects.

Perhaps most tellingly, we now tolerate carbohydrates better when we do choose to eat them. After a higher-carb meal, we return to ketosis within a day or two, depending on the meal – a sign of restored metabolic flexibility rather than fragility.

That said, the transition isn’t always comfortable at first. People who have relied on carbohydrates as their primary fuel for years often experience so-called keto flu symptoms , including fatigue, headaches, weakness, lightheadedness, or brain fog, as the body relearns how to run efficiently on fat and ketones.

I’ve heard this repeatedly from people who say they “tried keto and felt terrible.” When I ask how long they stuck with it, the answer is almost always less than two weeks. That timing matters. For someone who hasn’t been in ketosis for years, or even ever, the early adaptation phase can feel genuinely unpleasant.

This phase reflects temporary electrolyte shifts, changes in fluid balance, and the upregulation of fat- and ketone-burning enzymes, not harm. With adequate hydration, sufficient sodium, and a bit of patience, these symptoms usually resolve within days to a couple of weeks. I cover this process in detail, along with practical ways to avoid common mistakes, in my full article on keto flu.

Fuel States: Glucose-Dominant vs Ketone-Dominant

| Feature | Glucose-Dominant State | Ketone-Dominant State |

| Primary fuel | Glucose | Fat & ketones |

| Insulin levels | Frequently elevated | Low and stable |

| Fat burning | Suppressed | Active |

| Energy availability | Variable | Steady |

| Metabolic flexibility | Reduced over time | Preserved / improved |

| Typical modern pattern | Constant | Rare |

What Happens When Carb Intake Is Very High?

High carbohydrate intake is not inherently dangerous in isolation. The problem arises when carbohydrate intake is consistently high, meals are frequent, and the body is rarely given time to leave glucose-dominant metabolism.

The liver, which plays a central role in regulating blood sugar, can store only about 80-100 grams of glycogen, the stored form of glucose. By contrast, the average Western diet provides roughly 250-300 grams of carbohydrates per day. In practical terms, this means glucose availability is constantly replenished, often long before liver glycogen stores are meaningfully depleted.

In this state, blood glucose is repeatedly elevated and insulin remains chronically active. Insulin’s job is to manage incoming glucose, but it also suppresses fat burning and signals energy storage. When this signaling never fully shuts off, the body becomes increasingly reliant on glucose and progressively worse at accessing stored fat.

Over time, this leads to a loss of metabolic flexibility. Fat oxidation is downregulated, ketone production is rarely engaged, and the body becomes dependent on regular carbohydrate intake to maintain energy. Hunger tends to rise, energy becomes more volatile, and longer gaps between meals feel increasingly uncomfortable.

Repeated glucose spikes also come with oxidative and inflammatory costs. Every rise and fall in blood sugar generates reactive byproducts, and when this cycling happens multiple times per day for years, it places a cumulative burden on metabolic systems. The issue is not a single high-carb meal – it is the absence of recovery time afterward.

In younger, highly active, insulin-sensitive individuals, this state can persist for a while without obvious consequences. Muscle tissue acts as a glucose sink, and excess energy is more easily cleared. But as activity declines, stress increases, or insulin sensitivity erodes with age, the same intake becomes harder to manage.

Eventually, high carbohydrate intake stops being merely tolerated and starts becoming self-reinforcing. Insulin resistance rises, fat storage becomes easier, fat access becomes harder, and the body becomes locked into glucose dependence – not because glucose is required, but because alternative fuel pathways are no longer regularly used.

The problem, then, is not carbohydrates themselves. It is a metabolic environment in which carbohydrates are never absent, insulin is never fully low, and the body is never required to switch fuels.

That condition – constant glucose availability without interruption – is historically novel, biologically mismatched, and central to many modern metabolic disorders.

Can Healthy People Eat Carbs Without Issues?

Yes, some healthy, insulin-sensitive people can eat carbohydrates without immediate or obvious problems. Youth, regular physical activity, and higher muscle mass all increase the body’s ability to clear glucose efficiently. In these conditions, carbohydrates are more likely to be stored as glycogen and burned rather than spilling over into fat storage or chronic hyperinsulinemia.

But tolerance is not the same as benefit.

Even in healthy individuals, carbohydrates do not provide a unique metabolic advantage over fat and ketones for long-term health. Ketones are simply handled more gracefully. Blood sugar rises are smaller, insulin returns to baseline more quickly, and metabolic flexibility is preserved.

Historically, this tolerance was reinforced by natural constraints. Carbohydrates were seasonal, physically demanding to obtain, and often paired with periods of scarcity. In that context, glucose use was episodic, not constant. Modern food environments remove those constraints entirely, making it easy for even healthy people to drift into continuous glucose dominance without realizing it.

The problem is that metabolic health is not static. Activity levels change, stress accumulates, sleep declines, and insulin sensitivity gradually erodes with age. A carbohydrate intake that is easily tolerated at 25 can become problematic at 40 – not because the person suddenly became unhealthy, but because the buffering systems that once protected them are no longer as robust.

This is why “doing fine on carbs” should not be confused with carbohydrates being metabolically necessary or protective. Many people tolerate carbs for years before subtle signs of dysfunction appear – rising fasting insulin, creeping weight gain, energy volatility, or reduced fat-burning capacity.

Healthy people can eat carbohydrates without immediate issues. That does not mean carbohydrates are required, optimal, or risk-free over the long term. It simply means the consequences may be delayed, especially in a world where carbohydrate availability is constant and effortless.

Carb Intake Contexts

| Context | Carb Role | Outcome |

| High-intensity sport | Useful | Performance boost |

| Seasonal / occasional intake | Tolerable | Recovery possible |

| Daily high-carb intake | Problematic | Chronic glucose dominance |

| Long-term low-carb | Supportive for many | Improved metabolic stability |

The Better Question to Ask

At this point, the question is no longer “How many carbs should I eat per day?” That question assumes carbohydrates are the default and that health depends on finding the right number.

A better question is whether carbohydrates are serving a purpose or simply occupying space.

Instead of focusing on grams, it’s more useful to ask:

- Am I spending enough time in a fat- and ketone-dominant state?

- Do carbohydrates improve my energy and metabolic markers, or destabilize them?

- Can I switch easily between fuels, or do I feel dependent on regular carb intake?

- Am I choosing carbs intentionally, or consuming them by default?

When you frame the decision this way, carbohydrate intake stops being a rule to follow and becomes a tool you can use (or not) depending on context. And for the vast majority, who spend more time in a desk chair than roaming the wild, a surplus of glucose over what the body naturally produces simply doesn’t make practical sense.

Final Thoughts

Dietary carbohydrates are not required for human health – and for most people in modern conditions, they are not metabolically neutral either.

Regular carbohydrate intake keeps the body locked in glucose-dominant metabolism, suppressing fat oxidation and preventing meaningful time in ketosis. Over years, this state tends to produce slow, cumulative damage: rising insulin resistance, chronic inflammation, and a loss of metabolic flexibility. The harm is not immediate or dramatic, but it is real.

This does not mean carbohydrates are acutely toxic or that eating them is a moral failure. It means they represent a trade-off. Carbohydrates can be useful for short-term performance or social enjoyment, but eating enough of them to consistently block ketone production is unlikely to support long-term metabolic health for most people.

The body was built to switch fuels, not to rely on glucose constantly. Ketosis is not an extreme state to fear – it is the condition that allows metabolic recovery to occur.

Carbohydrates should be a choice, not a default. And for most people, better health comes from choosing them far less often than modern diets encourage.

FAQs

How many carbs do you need per day to be healthy?

From a biological perspective, none. The body can produce all required glucose internally, and many people maintain excellent health with very low or zero carb intake.

Is it safe to eat very few carbohydrates long term?

Yes. Long-term low-carb and ketogenic diets have been used clinically for decades and are well tolerated when protein, fat, and micronutrients are sufficient.

Why do guidelines recommend 130 grams of carbs per day?

That number was based on estimated brain glucose use in people already eating high-carb diets — not on evidence that dietary carbs are required.