Carbohydrates are one of the most talked-about nutrients in modern nutrition — and one of the most misunderstood.

You’ll hear that carbs are the body’s main fuel, that you need them for energy, and that cutting them is dangerous. You’ll also hear the opposite: that carbs are uniquely fattening, inflammatory, or something to avoid altogether. Both sides tend to speak with confidence, and neither usually explains why.

This article is meant to slow the conversation down.

Rather than telling you how many carbs to eat or which diet to follow, the goal here is simpler: to explain what carbohydrates actually are, what they do in the body, and why so much confusion surrounds them.

If you’ve ever wondered why carbs affect energy, blood sugar, weight, or health so differently from fat and protein — or why nutrition advice about them seems to change every few years — this article will give you the context you’ve likely been missing.

Everything else becomes easier once the basics are clear.

What Are Carbohydrates?

Carbohydrates are one of the three macronutrients, alongside fat and protein. At a basic level, they’re compounds made of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen that the body can break down into glucose.

That sounds technical, but the practical takeaway is simple: carbs are a dietary source of glucose – a form of energy the body knows how to use quickly.

When people say “carbs,” they’re usually talking about foods like bread, rice, fruit, sugar, potatoes, and grains. In nutrition, these foods are grouped together not because they look alike, but because they ultimately deliver glucose into the bloodstream once digested.

Carbs are often described as the body’s “main” or “preferred” fuel. That phrasing is common, but it’s also part of why there’s so much confusion around them. Glucose is a useful fuel, especially for short-term or high-intensity needs, but that doesn’t automatically mean it’s the only fuel the body can run on – or that it needs a constant supply from food.

One thing that surprised me when I first dug into this topic is how little the basic definition of carbs actually tells you about whether you should eat them, how many you need, or what happens when you don’t. Understanding what carbs are is only the starting point – the real questions come from how the body handles them.

The Three Main Types of Carbs

Not all carbohydrates behave the same way in the body. From a nutritional standpoint, carbs are usually grouped into three broad categories based on their chemical structure and how the body digests them.

Sugars (Simple Carbohydrates)

Sugars are the simplest form of carbohydrates. Chemically, they’re either single sugar molecules or very short chains, which means they’re absorbed quickly and tend to raise blood glucose rapidly.

Common examples include the following sugars:

- Glucose (the sugar already circulating in your blood)

- Fructose (the primary sugar in fruit and honey)

- Sucrose (table sugar, made of glucose + fructose)

- Lactose (milk sugar, made of glucose + galactose)

Because these sugars require little to no breakdown before absorption, they deliver energy fast. This is why sugary foods often cause quick spikes in blood sugar – followed by equally quick drops.

This is what people are usually referring to when they talk about “simple carbs.”

Starches (Complex Carbohydrates)

Starches are longer chains of glucose molecules linked together. Foods like bread, rice, pasta, potatoes, and grains fall into this category.

These are commonly labeled “complex carbs” because their structure is more complex than sugars. However, this term can be misleading. During digestion, starches are still broken down into individual glucose molecules — they just take a bit longer to get there.

In other words, starches and sugars ultimately end up as the same thing in the bloodstream: glucose. The main difference is how quickly that glucose appears, which depends on factors like processing, cooking, fiber content, and portion size.

So while “complex” sounds healthier, it doesn’t automatically mean low impact.

Fiber

Fiber is also classified as a carbohydrate, but it behaves very differently from sugars and starches. Most fiber passes through the digestive system without being broken down into glucose, which means it has little to no direct impact on blood sugar.

Because of this, many foods subtract fiber from their total carbohydrate count and advertise “net carbs.”

Net carbs are typically calculated as:

Total carbohydrates − fiber = net carbs

So if a product lists 20 grams of total carbs but 15 grams of fiber, it may be marketed as having 5 grams of net carbs.

The idea behind this approach is that fiber doesn’t meaningfully contribute to glucose load, so it’s excluded when estimating how a food affects blood sugar or ketosis.

That said, net carbs are a simplification, not a perfect measure. Some fibers are partially fermented by gut bacteria, some sugar alcohols behave differently than expected, and individual responses can vary. Net carb labeling is best viewed as a rough guideline rather than a guarantee.

Still, the concept highlights an important point: not all carbohydrates raise blood glucose in the same way. Fiber-rich foods — or products with added fiber — can look very different metabolically from their total carb number alone.

For an in depth assessment of the differences between simple, complex, and refined carbohydrates, see this article here.

Types of Carbs and How They Behave

| Type of Carb | Examples | Digestion Speed | Effect on Blood Glucose | Key Notes |

| Sugars (Simple) | Glucose, fructose, sucrose, lactose | Very fast | Rapid rise | Minimal digestion required |

| Starches (Complex) | Bread, rice, pasta, potatoes | Moderate | Moderate–high | Broken down into glucose |

| Fiber | Vegetables, seeds, psyllium | Very slow / none | Minimal | Not converted to glucose |

What Happens in the Body When You Eat Carbs

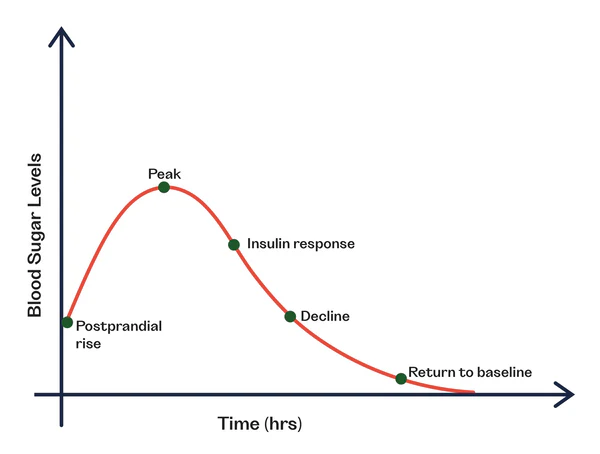

When you eat carbohydrates that can be digested – mainly sugars and starches – they’re broken down into glucose during digestion. That glucose enters the bloodstream, where it becomes available for immediate use.

As blood glucose rises, the pancreas releases insulin. Insulin’s job is simple: move glucose out of the bloodstream and into cells, where it can be used for energy or stored for later. Some of that glucose is burned right away, particularly if you’re active. Some is stored as glycogen in the liver and muscles. Once those storage sites are sufficiently full, any excess is more likely to be converted into fat.

This process is normal human physiology. Glucose and insulin are not inherently harmful. They’re essential parts of how the body manages energy. The issue isn’t that this system exists – it’s how often it’s activated.

When carbohydrates are eaten frequently, blood glucose and insulin are repeatedly elevated throughout the day. The body spends most of its time processing incoming glucose rather than relying on stored fat or alternative fuel systems. Over time, glucose becomes the default fuel not because it’s required, but because it’s constantly available.

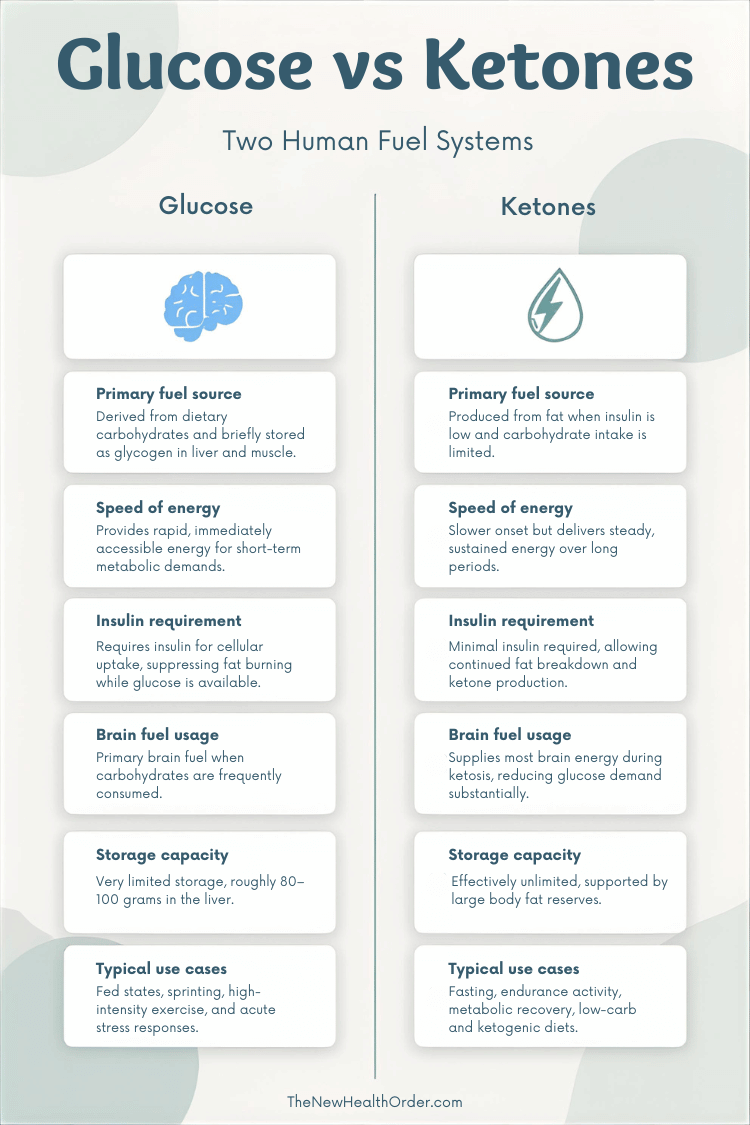

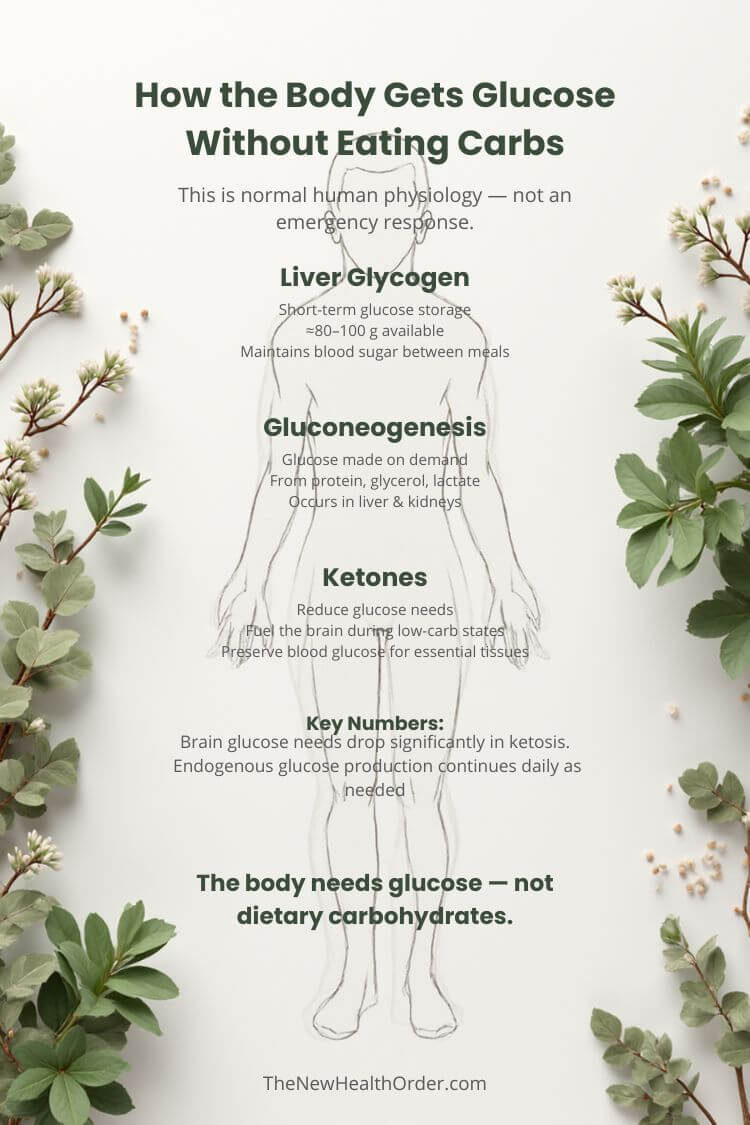

What’s often missing from this explanation is that glucose is not the body’s only fuel option.

When carbohydrate intake is low – or when enough time passes between meals – the body can shift toward burning fat and producing ketones, small energy molecules made in the liver from fatty acids. Ketones can supply energy to most tissues in the body, including the brain, which reduces the overall need for glucose.

This glucose-based and ketone-based system isn’t a backup or emergency mode. It’s a built-in feature of human metabolism. The body is designed to move between these fuel pathways depending on availability, using glucose when it’s abundant and fat and ketones when it’s not.

In modern diets, where carbohydrates are eaten often and throughout the day, this second fuel system is frequently underused. Not because it’s unnecessary, but because the body rarely gets the chance to engage it. And science is increasingly showing that there are a whole host of health benefits from spending time in ketosis.

Understanding this sequence helps explain why carbs can feel energizing in the short term, yet problematic when they dominate the diet long-term. It’s not a single meal that matters, but the metabolic state the body spends most of its time in.

Glucose vs Ketones as Fuel Sources

| Feature | Glucose-Based Fuel | Ketone-Based Fuel |

| Source | Dietary carbs or glycogen | Fat (dietary or stored) |

| Speed of energy | Fast | Slower, steadier |

| Insulin required | Yes | Minimal |

| Brain fuel | Primary in high-carb diets | Major fuel in ketosis |

| Typical use case | Short bursts, high intensity | Baseline, endurance, fasting |

What Do Carbs Do in the Body?

At a basic level, carbohydrates provide a fast and accessible source of energy. Once converted to glucose, they can be used immediately by cells that prefer or require quick fuel, particularly during short bursts of activity.

Carbs also play a role in glycogen storage. When glucose isn’t needed right away, it’s stored in the liver and muscles as glycogen. Liver glycogen helps maintain blood sugar between meals and overnight, while muscle glycogen supports physical performance during intense or repeated efforts.

In certain contexts, carbohydrates can enhance performance. High-intensity exercise relies heavily on glucose, and having glycogen available can improve power output, sprint capacity, and recovery between efforts. This is one reason athletes and highly active individuals often tolerate higher carb intakes more easily.

Carbohydrates also influence hormonal signaling. Insulin, released in response to rising blood glucose, doesn’t just manage sugar levels — it also affects fat storage, fat burning, and how the body partitions energy. Frequent carb intake keeps insulin active, shaping the metabolic environment over time.

It’s important to note what carbs don’t do. They don’t provide essential building blocks in the way protein does, and they don’t supply essential fatty acids or fat-soluble vitamins. Their primary function is energy delivery and storage, not structural repair or micronutrient provision.

We shoudl think of carbohydrates as a tool. They supply quick energy, support certain types of physical performance, and influence how the body manages fuel. Whether those effects are helpful or harmful depends less on the carbs themselves and more on how often they’re consumed and what metabolic state the body spends most of its time in.

Why Carbs Became Central to Modern Diets

Carbohydrates didn’t rise to prominence because they were proven to be essential. They became central because they were available, scalable, and economically efficient – long before modern nutrition science existed.

The shift began as early as the Industrial Revolution in the 18th and 19th centuries. Advances in agriculture, milling, and food processing made refined grains and sugars cheaper, more abundant, and more shelf-stable than animal foods. For the first time in human history, large populations had consistent access to cheap and concentrated calories.

This trend intensified during the World Wars, when meat and fat were rationed and governments actively promoted grains and starches as practical substitutes. These weren’t nutritional recommendations in the modern sense – they were logistics decisions made under scarcity. But they shaped dietary habits that persisted long after the wars ended.

By the mid-20th century, carbohydrates were already a dietary staple when formal nutrition guidelines began to appear. As concerns about heart disease grew in the 1950s–1970s, dietary fat (particularly saturated fat) was increasingly blamed, despite weak and inconsistent evidence.

This shift didn’t happen in isolation.

This shift away from fat was based on assumptions that haven’t held up under closer scrutiny. I break down that evidence – and where it went wrong – in Is Saturated Fat Bad For You?

As fat intake was pushed down and protein intake was implicitly capped, calories had to come from somewhere. Carbohydrates were the only remaining option.

Common Misconceptions About Carbs

Much of the confusion around carbohydrates comes from a handful of ideas that sound authoritative, get repeated often, and are only partly true – or true in a very narrow context.

Clarifying these misconceptions goes a long way toward understanding why carbs inspire so much debate.

“Carbs Are the Body’s Preferred Fuel”

This is one of the most common claims, and also one of the most misleading.

Glucose is often described as the body’s preferred fuel because it’s easy to use and readily available when carbohydrates are eaten. But “preferred” here really means convenient, not biologically superior or required.

The body will use glucose first when it’s abundant because it’s efficient to do so. That doesn’t mean other fuel systems are inferior or dormant. When glucose availability drops, the body smoothly shifts toward burning fat and producing ketones, supplying energy without impairment.

Preference, in this case, reflects availability – not necessity.

“Carbs Are Essential for Health”

In nutrition, essential has a specific meaning. An essential nutrient is one the body cannot make on its own and whose absence leads to a predictable deficiency or disease. For example:

There are essential amino acids, fatty acids, and vitamins and minerals. But there are no essential carbohydrates.

This doesn’t mean carbohydrates are harmful or useless. It simply means the body does not require them from the diet to function, provided protein and fat needs are met. Glucose itself is essential, but dietary carbohydrates are only one way (not the only way) to supply it.

“Your Brain Needs 130 Grams of Carbs Per Day”

This idea comes directly from official dietary guidance and is often presented as settled science.

In the early 2000s, the Institute of Medicine introduced a Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) of 130 grams of carbohydrates per day. This number is widely cited as proof that carbs are required. But the reasoning behind it is rarely explained.

The figure was based on estimates of average brain glucose use in people already eating high-carbohydrate diets, with an added safety margin. It was not derived from evidence showing that lower intakes cause harm, nor was it meant to imply that glucose must come from dietary carbs.

In fact, the same report acknowledged that glucose can be produced internally through gluconeogenesis.

What’s more, decades of metabolic research show that the brain’s glucose requirement drops significantly when ketones are available. Classic studies by George Cahill and others demonstrated that during fasting or nutritional ketosis, brain glucose needs fall from roughly 120–130 grams per day to closer to 40–50 grams, with ketones supplying most of the remaining energy.

This isn’t an emergency response or a pathological state. It’s normal human physiology.

The 130-gram figure reflects how much glucose the brain uses when running almost exclusively on glucose, not a biological minimum, and not a dietary requirement.

For a full in-depth look into how many carbs you actually need a day, see this article here.

Why There’s So Much Confusion About Carbs

If carbohydrates were simply good or bad, this conversation would have been settled long ago. The reason it isn’t is that carbs sit at the intersection of biology, population health, performance, and food culture — and each of those lenses tells a different story.

One source of confusion is that much of modern nutrition advice is based on population-level data, not individual physiology. Large observational studies can show associations between dietary patterns and health outcomes, but they can’t tell us how a specific fuel source behaves inside a human body. When those associations are turned into blanket recommendations, nuance is lost.

Another issue is that nutrition messaging often collapses short-term performance and long-term health into the same conversation. Carbohydrates can clearly enhance high-intensity athletic performance, yet that fact is frequently extended to imply that they are necessary or optimal for everyday metabolic health. Those are two very different questions, but they’re rarely separated in public advice.

There’s also the problem of simplified guidance. Public health recommendations are designed to be easy to follow at scale, not metabolically precise. Telling millions of people to base their diet on carbohydrates is far simpler than explaining fuel switching, insulin dynamics, or individual tolerance. Simplicity helps compliance, but it also flattens important distinctions.

Language plays a role as well. Terms like “preferred fuel,” “essential,” and “balanced diet” sound definitive, but they’re often used loosely. Over time, repeated phrasing hardens into belief, even when the underlying science is more conditional.

Finally, the modern food environment itself amplifies confusion. Carbohydrates today are not just whole foods eaten occasionally; they’re refined, concentrated, and constantly available. Advice developed in a very different food landscape is now being applied to an environment it was never designed for.

Put together, these factors create a perfect storm: advice based on averages, framed around performance, simplified for scale, and applied to a food supply unlike anything humans have previously experienced. It’s no surprise that people receive mixed messages — or that many feel better when they quietly experiment outside the guidelines.

Understanding carbs requires stepping outside slogans and asking a more basic question: not what we’ve been told to eat, but how the body actually works when different fuels dominate.

FAQs

What are carbs?

Carbohydrates are macronutrients that break down into glucose, providing a fast source of energy the body can use or store.

Are carbs essential for health?

No. Glucose is essential, but the body can produce it internally without dietary carbohydrates.

Are carbs bad for you?

Not inherently, but they often have negative health effects depending on quantity, frequency, metabolic health, and whether they crowd out other fuel systems.